Women at Nuremberg: Edith Coliver

Editor’s Note: Narratives surrounding the Nuremberg Trials overwhelmingly focus on the men. From U.S. Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson to the notorious Nazi leader Hermann Goering, the legacy of this landmark event in judicial history is framed by men, overshadowing the critical and diverse roles played by women.

USC Shoah Foundation is spotlighting the under-examined efforts of women at Nuremberg in an eight-part series of stories that each focuses on the contribution of a different woman. The stories were shared in a Jan. 30 public lecture titled “Women at Nuremberg” by Diane Marie Amann (University of Georgia), who came to work at the USC Shoah Foundation Center for Advanced Genocide Research as a fellow in January.

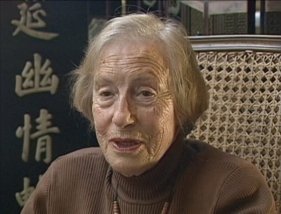

Edith Coliver

Edith ColiverWhen Edith Coliver landed a job to become an interpreter in the Nuremberg Trials in Germany, her parents were none too happy.

After all, the German-Jewish family had taken great pains to flee the country for San Francisco in 1938. And here she was, going back to the country that had kicked her out of middle school for being Jewish.

“My parents were not amused – they thought that we’d been through enough and seen enough and I didn’t need to go,” she said in the testimony she gave USC Shoah Foundation at age 77. “And I said I needed to go.”

Coliver, born Edith Simon in 1922, was highly qualified for the job. Not only had she spent the first 15 years of her life in Germany, she’d worked as an interpreter for the first United Nations Conference in San Francisco.

As an interpreter at Nuremberg, Coliver had a front-row seat to many historic moments. She was the interpreter who translated from English to German the famous opening statement for the prosecution, given by Robert Jackson on Nov. 21, 1945, in which he declared, “We must never forget that the record on which we judge these defendants today is the record on which history will judge us tomorrow.”

“I had to translate this into German, and I was scared silly,” Coliver said.

Time magazine, she said, described her as “the dark-haired interpreter whose voice quavers with the enormity of the situation.”

She says: “Well, it didn’t quaver because of that, but because I was scared silly about what I was doing.”

Coliver was also on duty for the testimony of the notorious Hermann Göring, creator of the Gestapo and a member of Hitler’s inner circle.

“He wasn’t particularly thrilled to have a female and a Jew as an interpreter,” she said.

A morphine addict ever since getting injured in the failed Nazi coup attempt known as the Beer Hall Putsch, Göring looked strung out, she remembered.

“He looked terrible because he was on drugs and they took his drugs away,” she said. “He was on withdrawal and lost about 100 pounds.”

During a break, Coliver did something she quickly came to regret: She asked Göring to autograph a book she had on Nuremberg.

“Afterwards I went out and thought, ‘My God, why did I give this man the honor of autographing a book?’”

In an attempt to rectify, she asked prosecutor Robert Kempner to sign the book below Göring’s signature.

Kempner wrote: “To Edith Simon, who helped hang the (above).”

As it happened, Göring – who was later sentenced to death – committed suicide by cyanide pill.

She remembers how the news was delivered by the prison’s security chief, who burst into the pressroom looking haggard: “The defendant Göring has cheated the gallows by doing away with himself.”

“All the journalists ran to their telephones,” Coliver said. “That was headlines.”

Before the end of the war, while attending college in the United States, Coliver had felt disassociated with her religion. But, she says in her testimony, “after Nuremberg, I felt I could never leave being a Jew. It would have been treason toward all those who died.”

After the trials ended, Coliver continued to work in human rights. She worked with Jewish refugees in a camp taken over by the U.S. Army, administered social, political and economic development programs through the Asia Foundation, and worked as the first woman to serve as vice president of the World Affairs Council of Northern California.

She and her husband Norman Coliver – with whom she had a divorce – had two daughters. Coliver died at age 79 of pancreatic cancer in 2001.

Like this article? Get our e-newsletter.

Be the first to learn about new articles and personal stories like the one you've just read.