In memory of Auschwitz-Birkenau survivor and Holocaust educator Eva Kor

USC Shoah Foundation is saddened by the recent loss of Eva Kor, a Holocaust survivor who – along with her twin sister – endured cruel experiments conducted on her at Auschwitz, and, half a century later, sparked controversy by publicly forgiving the Nazis who tormented her and killed her parents and two older sisters.

She went on to found CANDLES Museum and Education Center in Indiana.

Kor, who was 85, gave her testimony to USC Shoah Foundation twice. The first, in 1995, was a traditional interview recorded on video and stored in the Visual History Archive – just like the other 50,000-plus Holocaust survivors who shared their stories for what was at the time a new organization founded by filmmaker Steven Spielberg.

The second, in 2016, was for Dimensions in Testimony, the Institute’s pioneering interactive-biography exhibit that enables people to ask questions that prompt real-time responses from pre-recorded video interviews with Holocaust survivors and other witnesses to genocide.

Kor’s Dimensions in Testimony interview is on permanent display at CANDLES.

Known for her signature blue suits, Kor never lost the accent from her native Transylvania, Romania, where she was born Eva Mozes in 1934. She also possessed a playful wit.

“Can you believe that today I can get chicken McNuggets near Auschwitz?” she tweeted the day before her death, in Poland, where she’d traveled to lead students on an annual tour through Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. “That would have been wonderful 75 years ago. They taste the same in every country and were delicious.”

As 10-year-old girls, she and her sister, Miriam Mozes – who died in 1993 – had been among the twin children to serve as experimental subjects at Auschwitz under the sadistic hand of Dr. Josef Mengele.

In one of the experiments, doctors drew several vials of blood from Kor's right arm – five or six, she said in her 1995 testimony – “to see how much blood a person can lose and still live.” They injected her left arm with a series of mysterious shots. She grew gravely ill.

Kor was then taken to a fenced-in area by the barracks outside, where children were sometimes told they could play.

“Who wanted to play?” she said. “Children who face life and death situations are no longer children, and they do not want to play.”

Instead, Kor looked up at the sky, and saw American fighter planes in the distance.

“The American airplanes would come, would make a huge yellow smoke circle in the sky,” she said in the testimony. “Nobody ever told me, but after a few times, I realized that that meant they are now going to bomb inside that circle. … That gave me hope that someday we might be free.”

Kor said she was determined to live, knowing that by surviving, she would also ensure the survival of her sister, Miriam: twins were a rarity, and therefore a scientific asset to Mengele.

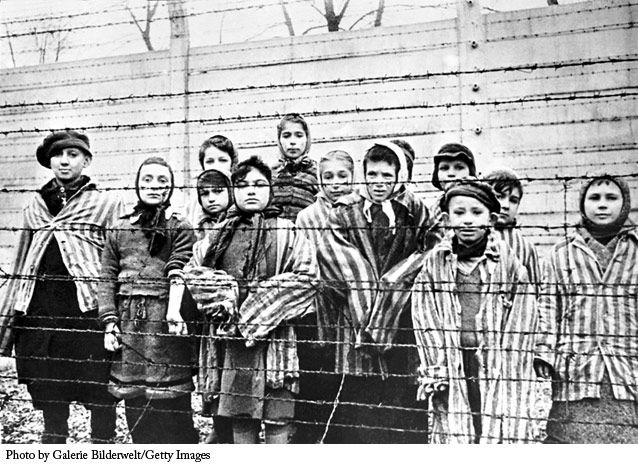

After the Soviet Army liberated the camp in 1945, the sisters were among 13 grim-faced children photographed behind the barbed wire. The image has become an iconic depiction of the Holocaust. In 2015, USC Shoah Foundation tracked down four of the grown children – Kor included – for a photo shoot of them standing behind a large rendering of the image.

In 1995, Kor and Hans Munch – a Nazi doctor – created a stir when they appeared together at Auschwitz for a joint public statement. Munch confirmed to the world what was already known: that Nazis used the gas chambers to commit mass murder. Kor read her statement of forgiveness.

Some Holocaust survivors accused her of speaking for them. Kor said that was never her intention.

Rather, she has said, it offered a kind of second liberation – from victimhood.

“What I discovered for myself was life changing: that I had the power to forgive,” she said in an interview for a blog post by a USC Shoah Foundation staff member in 2015. “I refuse to be a victim. … Every victim has a human right to be free from what was imposed on them.”

She is survived by a son, Alex Kor; a daughter, Rina Kor; and her husband, fellow Holocaust survivor Michael Kor.