Introduction

Most of us have been sheltering in place for months now, waiting for life to reopen and for a feeling of security, safety and comfort to return. Some of us are alone; others are at home with children, pets, a partner, a roommate, or perhaps are caregiving for a parent. We are all experiencing something together, something that unites us and yet we often are facing very different realities.

Back in March, when shelter-in-place orders began, we at USC Shoah Foundation started to think about the concept of home and what it meant at its core. It sounds so simple to say “just stay home,” but we know it’s not. At the Institute we house over 55,000 testimonies from survivors and witnesses of genocide who speak to this concept — the idea of home. For most of them, home was a place that they were forced to flee. Home became an idea and a place they hoped to recreate again. For many, it was a place one could never return to again. Their vulnerability and their storytelling inspired us to want to explore this idea with you.

So, in honor of April being genocide awareness month, we began the What is Home Project. We asked you to respond to the following prompt: What does home mean to you during this difficult time? Home doesn’t have to be four walls. Home is an idea, a concept, a place of being. Home can be a song, a person, a smell. It can be an action, a story, a dream for the future. Home isn’t always gentle. Sometimes it is challenging, maybe even frightening. Sometimes it is a place you want to run away from and sometimes it is a place from where you are forced to flee. Sometimes home moves with you and sometimes you never go back. Home may be the family you were born into, or it may be the one you create. Sometimes home is noisy or crowded, or it may be just you. Maybe you enjoy the solitude, or maybe you feel lonely.

We asked you to submit your stories to us. Each week in April, we offered a new theme: spaces/places, family, resilience and messages for the future, and we asked for your stories. The prompt was open-ended; submit photos, videos, drawings and poetry. We suggested spoken word and recorded sounds from home. We said it could be abstract or literal; it could be something created today or something from the past.

Your contributions were remarkable. We received dozens upon dozens of responses from around the world — from Morocco to Argentina to Switzerland, Israel, Canada, Poland and across the United States. Some of you shared that you even had family members in our archive. Individuals of all ages contributed — from as young as 14 years-old to college students to young professionals, to middle-age parents to grandparents. Artists sent in their drawings, writers sent in their words, and photographers sent in their pictures. There were old family photographs and new images created in quarantine. There were poems and essays, thoughts revisited from the perspective of COVID-19 and ideas that spoke to our collective and individual past, present and future.

We want to thank everyone who contributed to this project and helped us collect this extraordinary testimony of today. We have selected and curated more than 20 entries below as part of our What Is Home Project, each one providing an intimate glimpse into what it means for people around the world to be home.

To Have A Place To Go…

To Have A Place To Go…

“To have a place to go, is to have a home. To have people you love, is to have a family. To have them both, is a blessing.”

“Tener un lugar a dónde ir, es tener un Hogar. Tener personas a quienes amar, es tener Familia y tener ambas es una Bendición.”

— Contributed by: Julie Sadofsky, Country Director for Outreach 360 / Monte Cristi, Dominican Republic

Cynamon

Cynamon

“I choose my Cat, Cynamon, because he always makes me happy and I feel really well with him. He is the Best Cat in the world.”

— Contributed by Maks Kowalik, 14 years old / Poznan, Poland

Books Are Home…

Books Are Home…

As far back as I can remember, home was defined by books. A sea of them, a cascade, piled on shelves and desks and counters and tabletops. One year my father even built a bookshelf that he designed himself, in the mid-century modern style of the Scandinavian furniture he and my mother had purchased, in honor of their having met in Sweden as refugees. Echoing the old IBM slogan, THINK, that hung on the wall of my father’s study (a sign I now have in my own study), my father trusted books to keep him safe in the world. This was especially true after his Jewish school was shuttered by the Nazis, forcing him to find ways to keep learning on his own, and therefore ravenous for any book he could get his hands on.

Is it any surprise I became a writer? To grow up surrounded by books as a version of family treasure surely convinced me that the most valuable contribution I could make was to write books of my own. Contribution being the key word here too, of course. With the constant reminder that 1.5 million children had been murdered in the Holocaust, and that their loss was an infinity of lost contributions, I knew it was my obligation to try to make up for that absence. I keep writing to fill in those blanks: on the page and on the world that those books will, if I am lucky, come to inhabit.

— Contributed by: Elizabeth Rosner, Author of Survivor Café / California, USA

Home

Home

A few years ago, I read an article about a young girl who was born in a refuge camp. She was older now, and writing about the idea that home for most people is usually where they “start”. But for those that don’t start somewhere permanent, what is home? What if you were born in a place that once was? A place that doesn’t even exist by current map standards. What if a country doesn’t claim you? Ive always known I grew up in a home. A complicated one at times, but a home. Until this article, I had known of the concept of statelessness but not the concept of no beginning.

So what is home? I was tasked by the wonderful @Rachael to consider submitting to the #whaishomeproject. I sat on it for weeks and realized home for me has so many faces. Each with their own menu of expressions. There was the childhood walls, floor, and ceiling. There was many pools I called home. There were ships in the ocean I called home. Now there’s a smorgasbord of airplanes, hotels, cities, states, and countries. But those are all places. Not concepts or people.

Home as a concept, for me, has morphed considerably over the years. When someone says they feel “at home”, typically it means they’re comfortable. I feel at home when I smell chlorine. I feel home when someone makes toast. I feel home when Im in a sweatshirt and sweatpants. And certain people feel like home. But I think home is the ability to combine the past, present and future, into your heart. Home is a comfort. Home is a mental safety that houses your deepest secrets, all the amazing and the terrible. I can be home, when I am completely alone with my thoughts. So that I can dream, reminisce, and grow. But would I be that way if it wasn’t for the original walls, floor, and ceiling?

— Contributed by Erica Robinson, photographer and National Technical Representative for Tamron USA / California, USA

Cuarentena 2020 / Quarantine 2020

Cuarentena 2020 / Quarantine 2020

This is where I meditate. The reflection of the bars are a metaphor of our actual condition; staying indoors and not allowed to go out as indicated by the country where I live.

— Contributed by: Carola Aisiks / Buenos Aires, Argentina

What happens when you are required to reject the idea of home from the beginning of life?

What happens when you are required to reject the idea of home from the beginning of life?

Just being able to formulate that question has required nearly twenty years of writing and research and a lifetime―in my case, 53 years―of reflection about the way things were unfolding.

But let us start in the year 2000 when my husband and I decided to realize a long-time dream of his, which was to spend one year in his charmingly flawed summer cottage on an isolated island outside Stockholm, which he had inherited from his grandfather. The island was essentially a pile of rocks, the tip of an ice age mountain ridge, with a modest cottage, where sand miners had settled with their families during the early 19th century, and some small ancillary houses and sheds built much later.

I was the instigator of this project and intent upon seeing it through at every step of the way, despite or perhaps because of my utter lack of knowledge about living off-grid in a Scandinavian wilderness, with all of the challenges that living on an island through the winter presents. My husband certainly hadn’t considered pursuing his dream with his new young wife, who had never lived outside of an urban environment before and toddler twins, a boy and a girl, whose natural curiosity drew them to the water and the ice. As with many of the things we do, we don’t really know why we are doing them until long after the fact. As I learned more I began to awaken to the risks, but to me this project was like fighting for life itself.

One year turned into nine in which we lived, worked and raised our children on the island. It was the happiest time of my life to date, perhaps because I was learning what home felt like and what it meant to be at home. Knowing where certain wildflowers popped up every year, how the air smelled, and what the endearing imperfections of our house were changed my outlook fundamentally.

Most important of all was the realization that life didn’t have to be as it had been before: A constant uprooting of the finest thin tendrils that had begun to grow in each place I lived in growing up as a child. Ten countries, three continents in those seventeen first formative years naturally led to the perception that there was no other model. As a young adult I became a consultant in the developing world, and thus my suitcase was always at the door. Home seemed an irrelevance until at the age of twenty-nine this fragile construction of a life stopped working for me.

When the children turned eleven, we moved back to the mainland as the small village school they had been attending across the lake only went up to 6th grade. Life on the island had grounded me and at the same time become the incubator of questions about the past. Why had things been the way they were in my old family? Sometimes it seemed like we were running so fast that we must be trying to escape. As it turns out, both of my parents were trying hard to leave their quite different pasts behind. I cannot judge them for this. Neither of them was handed an easy deck.

Today, after a decade of research into my mother’s family’s past, I realize that in some perspectives we were running away from something very serious, at least in the conversations that led nowhere except to conflict. In 2010 those conversations had deteriorated to a point where I felt it necessary to visit the German Federal Archives in Berlin, and there began a long process of learning that my grandparents were an SS couple in occupied Poland throughout the duration of World War II, fleeing to Latin America in 1960 when a new wave of war crimes trials had commenced in the Federal Republic of Germany.

It was a terrible if not impossible legacy to reckon with, but suddenly everything began to make sense: the rootlessness, the extensive efforts to maintain it, and the questions that arose as life in this state began to unravel. The years of research took me to Germany, Poland, Paraguay and Brazil, my birthplace, which I had left at the age of three and had divided feelings about because of the angry emotions it evoked in my mother’s family. I spoke fluent German, mainly as a result of teaching myself the language and speaking to my grandmother; but that country too, despite many visits with family, had remained a troubling concept in my existence. Going back to these places with open eyes about the facts and a hunger to learn rather than living in denial, helped me to reconcile with these cultures that furnished my inner home, and make peace with them. Although there were many calls for me to stop this work and "let past be past," the people I met along the way, even family I hadn't known existed (see excerpt, below), confirmed for me that this was the most important thing I could do.

The search for home is never-ending, like the peeling of the onion, as Nobel Laureate Günter Grass put it in his memoir of the same name, in which he disclosed that as a youth he was recruited into the Waffen-SS in the war’s closing phases. For me the search goes on, but I find myself less at war with it, at times in deep sorrow, but always in wonder.

— Contributed by Julie Lindahl, Author of The Pendulum: A Granddaughter's Search for her Family's Forbidden Nazi Past and co-curator of The Creative Conversations

It’s The first night of Passover…

It’s The first night of Passover…

“Sometimes stories are sad. Still, it is important to tell them and retell them, to live them again and again, this year and next, when we shall meet again around this Seder table.” - Holocaust Elie Wiesel wrote in his rendition of the Passover Haggadah.

It’s the first night of Passover, the first seder, and I’m about to get on Zoom to video call into a meal with my family. About 22 of us will “zoom in” from different areas in New York, Florida, Texas, and [me, here in] Boston. It has been really hard moving away from my family, especially in these times. But this quote reminds me that sometimes not everything can be what we expect, sometimes things are sad, but we must go on. And next year, I hope, we’ll all physically be together, saying, “Remember last year when we had to do the zoom call?”

— Contributed by Shira Stoll, documentarian behind Where Life Leads You / Massachusetts, USA

The photo that initiated our personal project about my grandfather…

The photo that initiated our personal project about my grandfather…

“We cherish every photo we find of our family, as most of our family photo albums were lost. Every time we find another photo it is an emotional event for us. It is like bringing the family back together. The following photos were found in a box after we started our discovery journey. As we look at each photo we discover another story of our family’s past. This, for us, is HOME.“

— Contributed by: Idit Kobrin, creator of Stories Hidden In Boxes / Basel, Switzerland

What I Was Beginning to Learn

What I Was Beginning to Learn

In this time of uncertainty and despair, we need inspiration and hope.

One person who has taught me a lot about humanity is Dr. Baher Butti, an Iraqi refugee. Dr. Butti was the director of Al Rashad psychiatric hospital in Baghdad. He was also an activist who was put on a kill list and forced to flee the country that he loved.

I have since worked closely with Dr. Butti on my “What We Carried: Fragments and Memories from Iraq and Syria” project. He became my cultural mentor and friend. Sometimes I refer to him as “my Iraqi brother.”

We have collaborated on several other projects and events, including an exhibition and poetry reading titled “Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here!” This project was a reaction by Bay Area poet Beau Beausoleil to the car bombing of Al-Mutanabbi Street, the historic booksellers street in Baghdad.

We have exhibited “Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here!” events in Portland. I remember one small bilingual poetry reading a few years ago. We read poems in English and Arabic to an audience of about 50 people. I read a couple of my “What We Carried” writings.

Later, it was Dr. Butti’s turn. As he approached the podium, he kinda mumbled something almost under his breath to quietly introduce himself. He said something like this: “My name is Baher … and I’ve been working for peace all of my life, and I know it’s a peace that will never come.”

I wasn’t sure if I heard him correctly. A peace that will never come?

First, I thought he was expressing the futility of working for peace. Was he expressing hopelessness? As he read his poems, I couldn’t get those words out of my thoughts.

As I thought deeper, I realized what he clearly understood, and what I was just beginning to learn: Of course, there will never be a time when we will have total peace on earth.

But working for peace is still our mission — to try to make a better world.

Working for peace is our mission.

— Contributed by: Jim Lommasson, photographer What We Carried / Oregon, USA

This ‘What Is Home Project’ has been very therapeutic for myself.

This ‘What Is Home Project’ has been very therapeutic for myself.

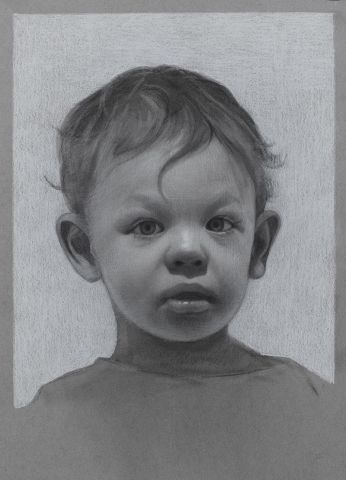

As a painter I get to slow down life so that I can spend more time learning about lives that I find intriguing, as well as a way to bring loved ones that are far away closer to me by spending lots of time with them, painting them. But during this worldwide crisis, I have been a little worried about my freedom to paint/draw personal subjects because of a fear of not having collectors and losing my income from in person teaching workshops. The feeling of painting something sellable is pervasive for self preservation to just be able to create. That said, taking the time to slow way down and think more about my original intentions through the What is Home project as an artist was a helpful break I needed. I used to travel a lot and used to live in Brooklyn and Albuquerque NM at the same time, having homes in both places and loved ones in both places. I had reasoned with myself that the place never mattered but the company I had in each spot was my home. So the subject of my contribution to this project was pretty easy to think of, My son Lucas, who is now 13 years old turning 14 in a few weeks. He has been separated from us during this outbreak, having been last in New Mexico this passed February. I had planned a few trips out to Brooklyn each month to see him and have had cancel those trips for now. We do get to play online games together and talk via FT each day, but I still miss him. Of course, I'm insanely lucky during this time compared to many others that my heart goes out to and I'm doubly lucky that as an artist, I get to sink myself into a drawing of someone I miss so much. I get to bring him closer to me in spirit by drawing him, charcoal mark by charcoal mark.

— Contributed by David Kassan, Visual Artist behind Facing Survival:David Kassan

Together, Restoring Their Names

Together, Restoring Their Names

I am a senior at Brandeis University. In 2015, I created Together, Restoring their Names, which is a Holocaust memory service-learning program for students of all backgrounds in Boston. During their educational fellowship, students travel to Europe to learn about the Holocaust. Upon returning to Boston, fellows volunteer with Holocaust survivors, lead educational programs on campus, and work on research projects. In these #WhatIsHomeProject videos, students reflect on their connections to the Shoah and what it means to them. Throughout these videos there is a motif that rings true for me. It is a lesson of appreciation. I've been fortunate through this experience to have been invited into the homes of many Holocaust survivors. Their homes are safe havens, just like yours and mine, in a world that does not always provide safety to all. In these trying times, I am grateful that we have the safe haven of home.

— Contributed by Elan Kawesch, creator of Together, Restoring Their Names / Massachusetts, USA

This is only one small part of my mom’s story…

This is only one small part of my mom’s story…

This is my mom with her brother and mother right before her mom was deported and never to be seen again. She died in Auschwitz.

This is only one small part of my moms story. I am sharing it now because, her own family is finding the strength and resilience during this pandemic because of what my mom went though as an 11 year old. Charlottes grandchildren recently said, "if my meme could be confined to a cellar for 9 months, with nothing but a cot, kerosene lamp and a bucket for her waste, we could endure the “stay at home” restrictions and social distancing” for however long it takes.

While she was in a cellar during the war, the Quatreville family cared for her and essentially saved my mom's life. Thy searched and searched till they found my mom through Facebook in 2016. In 2018 we were all reunited in Paris as one big family. They are an extension of our family now and we all keep in touch regularly. During this time when my mom is at home, she remembers her time in the cellar and this family. It is never far from her thoughts. She stays strong because of family. When her thoughts go dark during this time of isolation, she loves to look at photos of our reunion trip to Paris and photos of the life her and my dad created. They were married for 50 years and she is very grateful for the life she has, even during these times.

— Contributed by: Roz Goldberg / USA

My Grandmother Wrote Quite Often About This Grave…

My Grandmother Wrote Quite Often About This Grave…

This is my mom cleaning a family grave in Kolín, Czech Republic — the quiet town where my grandmother was born. She and I visited this place together in April of 2014. We were welcomed by community leaders and journalists, including the mayor. Everyone was interested in what we had to say, to be back to the place where our family was from. In a way we were proof to these locals that Jewish people did in fact once live here.

My grandmother wrote quite often about this grave which belonged to her paternal grandfather. She wrote, “He is the only one of the entire family who had a funeral and a grave. We planted a blue spruce at his grave site. The rest of the family was eventually murdered in concentration camps. The house of my grandparents is no more. The Jewish cemetery is no more. During the war the Nazis decimated it, using the grave stones for paving roads. Only the blue spruce, planted at my grand father’s grave survived.”

- Contributed by: Rachael Cerrotti, Storyteller in Residence at USC Shoah Foundation and creator of We Share The Same Sky Podcast / Massachusetts, USA

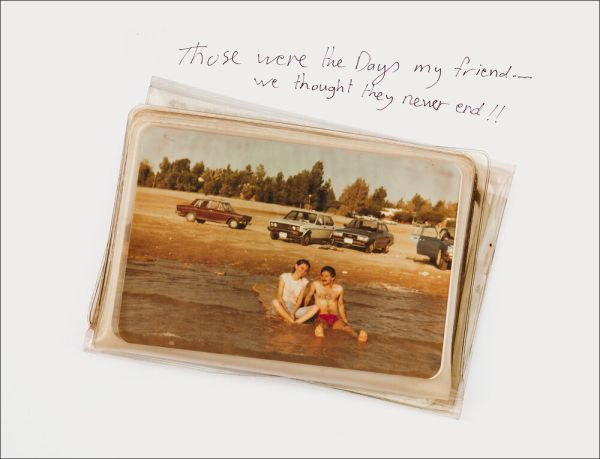

My wife and me from 1992, our first year together…

My wife and me from 1992, our first year together…

“We have been each other's home for nearly three decades out of the five since Stonewall. Whether living in Chicago or St. Charles, Illinois, or Montclair, New Jersey or Bangalore, India or in hotels and shipboard rooms around the world during our travels, wherever we are together is home.”

— Contributed by: Sarah Siegel / New Jersey, USA

Family Ezequiel / Family Margaret

|

|

|

— Contributed by Ezequiel and Margaret, third cousins from Buenos Aires and Boston, respectively. They connected for the first time in 2015 after Margaret watched USC Shoah Foundation’s testimony of Hans Lindenberg, Ezequiel’s grandfather, and have been retracing their shared family history ever since. |

|

Gravel fragments from the courtyard

Gravel fragments from the courtyard

of the apartment building where my grandma grew up. Where she spent her childhood, in Sárvár, Hungary, until the deportations. I brought them home and put them in the garden. They remind me that one day I'll have to tell my daughter the whole story.

- Contributed by Mike Turner, documentary filmmaker / Oregon, USA

One evening in the summer of 1942 in Częstochowa…

One evening in the summer of 1942 in Częstochowa…

the whole family including ‘Auntie’ Helena (my nanny had gone home by then) gathered around me to ask a question. With whom would I rather go to be delivered to my parents: Auntie Helena or my nanny? It was clear, I wanted my nanny, but what six year-old could look Auntie Helena in the eyes and say he preferred the other? The conversation continued.

“Granny, why don’t you come with me, I would love it so much?”

”I can’t. Grandpa has a long nose they would recognize him immediately as a Jew.”

”Then leave him here and come with me. Please!”

With Auntie Helena we took a train to Warsaw. I was told to pretend I was deaf and mute, and not to speak to anybody under any circumstances, my accent would betray me. And so I spent two hours glued to the window. Auntie Helena, in her own peasant singsong that she retained forever was chatting for these two hours with all the female occupants in the carriage. We then changed to a narrow gauge suburban train to Wawer, then a small village where my parents took shelter.

This was in July, and afterward as a grown up I learned that two months later on September 22, 1942 the Częstochowa ghetto was liquidated. My four grandparents all were sent to the gas chambers in Treblinka independently of the length of their noses.

— Contributed by: Wlodek Proskurowski, USC faculty, Emeritus Professor of Mathematic / California, USA — born in 1936 in Warsaw, Poland

I use photography as a means of documenting…

I use photography as a means of documenting…

my own experiences as they overlap and intertwine with the life worlds around me. My images are typically an expression of the people and places that I have come in contact with and the ways in which these moments and meetings have impacted my own narrative. Additionally, I have used photography as a tool to make the diversity of human experiences, more accessible and understood to others.

This is the first time that I have been in one place for more than two weeks in nearly a year. In the past ten years, I have moved regularly. I have lived in Taiwan, China, Egypt, Morocco, Switzerland, and the US – in each place for around one year. In other places, I have spent months or weeks at a time.

I am inspired to capture emotion and the relationship that people have with spaces and places, including myself. I see my photographs as a form of journaling and keeping a “home” while living with such a nomadic lifestyle.

I combine my work in experiential global education with photography. Working for an organization that leads groups of students in immersive education programs abroad, I spent most of 2019 in China and Morocco. At the start of 2020, I had just begun a new position as our "China Partnership Program Specialist" and had spent two weeks in China getting settled there before returning to the U.S. for a work conference. During those two weeks, COVID-19 hit China hard. All of my programs in China were cancelled and I was unable to return. I was stuck in the U.S. for a couple of weeks and lost a major portion of my work. Due to my previous experience working in Morocco, my position was shifted and by mid- February, I was instructing a group of students in a short-term program. The students left on March 11 and I was left with no more work and no more home (since my housing was attached to my work in China and I had moved out of my apartment in Chicago months prior). I was laid off of my job, many of my belongings left in China, and since Morocco shut down all international and domestic travel, I have found myself with no choice but to settle in here. A friend of mine who normally lives in Rabat, Morocco got stuck in Senegal and I have been able to stay in his studio apartment by myself.

Morocco has been under a strict quarantine since March 20. It is necessary to have a government authorization paper to leave the house for essentials and there is an enforced curfew of 6:00pm. Upon first arriving here, I felt extremely isolated in a city a I was relatively unfamiliar with and all alone. Photography has been an outlet, a home, and a therapeutic practice for me as a I cope with the realities of losing my job and home at once.

- Contributed by Kristen Gianaris, photojournalist, educator, and anthropologist / Rabat, Morocco

I wake up under someone else's roof, in someone else's bed, every morning.

I wake up under someone else's roof, in someone else's bed, every morning.

I toss and tumble between someone else's sheets. I stretch and sprawl on someone else's mat. I stand solemnly in their shower, water cascading down my neck and shoulders, as I cradle my weary head.

I exhale and make my way downstairs, where the coffee drips and the cereal pours. I take a sip. I take a bite. I open my computer and the day begins.

I've been in perpetual motion these past three years - over a hundred thousand miles across this country and across the globe. Home has been whatever I could carry and wherever I lay my head at night. I've seen so much of the world that I can humbly acknowledge, "I know nothing."

Now, I am stopped, stuck passing my days at someone else's dining room table and my evenings on someone else's living room couch. I traverse megabytes instead of miles, trying to stay connected with everywhere, everything and everyone I've come to know, through a 13.3 inch screen. My eyes strain and I am fatigued.

But spring is here. I'm reminded that the calm wind which catches me on someone else's balcony has traveled the world, as have the birds whose wings it has carried. They sing on the branches of trees that surround and I sit here, gently listening to the stories they tell. I'll be at home again soon.

— Contributed by Kenny Andejeski, Community Builder / Massachusetts, USA

My sister and I were raised by Holocaust Survivor parents…

My sister and I were raised by Holocaust Survivor parents…

who were deeply committed to teaching lessons of [their] family and community before, during and after the Holocaust. Relatively young, involved and focused, their journey included participation with local, National and International Organizations engaged in the teaching of history with a view of tolerance versus hatred and truth over revisionist falsehoods.

We were more fortunate than many of our friends who were denied extended family. For them Family was created by affiliation with local groups such as the “1939” Club and the Lodzer Organization. Friends became family, supporting one another at holiday celebrations and through life’s inevitable joys and sorrows. Though my husband’s family (also survivors from Poland) was miniscule and my parents lost many family members in Ghetto’s, Concentration Camps and Death Marches, a larger than average number of their nuclear family survived. Many weekends, vacations, holidays and major life events were celebrated with grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins. Survival and connection were woven throughout relocations from Poland to Germany to Canada, Israel and America.

Our parents were vocal about their experiences. Starting in the early 60’s Mom consulted with mental health professionals about ways the subject of their Holocaust experiences might be broached with two young daughters, to teach and not overwhelm. Over the years they discussed with us what they thought was age appropriate and answered our questions honestly. We watched WWII documentaries, movies and Newsreels followed by discussion of how what we’d seen supported their all too real experiences. They were early participants with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, UCLA Holocaust Documentation Archives and the USC Shoah Foundation for which I am grateful. My grandchildren and countless others may learn from the snippets of their lives.

With the exception of a paternal Uncle (99) and a maternal Uncle (97), both in remarkable mental and physical shape, all other elders are gone. As our extended families grew, gathering for holidays created “space” challenges. This time Covid-19 presented a unique opportunity using social media. Our [Canadian] cousin had his father officiate their Passover Seder, as he had done for more than 7 decades, and the rest of the family, stretching across the US and Canada, were “virtually” at the table with them. Many of us cried with the sweet memory of our own parents and grateful for just one more year to have this vital link. We can only hope to join him in celebration of our family next year at 100.

— Contributed by Carlin (Bruk) Glucksman / California, USA

It was no ordinary timepiece.

It was no ordinary timepiece.

While over the years numerous clock radios which had rested beside it had told the time of the day and night, set his alarm in the morning and ordered the present, this special clock held the time of the past.

In 1945, 75 years ago, Russian troops celebrated the 4th May Day of the Great Patriotic War. Hitler was dead. Berlin and all of Nazi Germany lay in ruins and the war in Europe was one week away from an end after six terrible years of death and suffering. And on the road in front of an SS Barrack in Rovershagen outside of Rostock on the Baltic Sea Coast of Northern Germany a straggling, starving, harassed near death column of Jewish Slave Laborers was liberated from the Nazi yoke by advancing Russian forces. My father and his cousin were among them.

His life was saved. He was free, but his world didn’t survive.

The Jewish Survivors desperate for food salvaged foodstuffs out of bombed out freight cars. In the rail yards opposite the barracks, there was margarine, speck, marmalade, sugar. The supplies were clearly marked as military stores and the local Germans still clinging to their craven Nazi ideology had not deigned to loot them. In a telling irony, it took the Haflings to distribute the Wehrmacht supplies to the starving populace.

Then in an undamaged railcar once broken open the Jewish ex-prisoners found a shipment of new military clocks in original boxes. No one was interested in them at all. They had no value except to my father. He alone took one and it remained steadfast by his side a witness to that bittersweet day of liberation and loss, of pain and hope, of despair and triumph. It stood a testament to his journey through the valley of the shadow of death. It counted his days as he rebuilt his life, started a family and moved on from his suffering to renewal and rebirth. He couldn’t forget that momentous day his personal nightmare ended. And that clock recorded the time of memory. It ticked as it always had through the seven days of Shiva after his death and I let it wind down and never wound it again. Its duty was done and now both it and its faithful owner silent.

- Contributed by Arlen Reinstein / Ontario, Canada

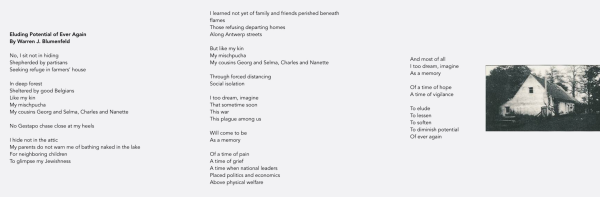

Eluding Potential of Ever Again

Eluding Potential of Ever Again

— Contributed by: Warren Blumenfeld, author of The What, The So What, and The Now What of Social Justice Education (amongst others) / USA

USC Shoah Foundation's contribution

USC Shoah Foundation's contribution…

to the 'What Is Home Project' are these survivor voices from our archive. They represent our four themes: Spaces/Places, Family, Resilience, and Future Generations.