Testimonies from 1937 Nanjing Massacre in China fully indexed and subtitled

In China, the number of people still alive who survived the 1937 Nanjing Massacre at the hands of Japanese invaders has fallen to minuscule levels – some experts put the number around 80.

USC Shoah Foundation’s collection of about 100 testimonies of survivors from this rampage that killed some 300,000 civilians and unarmed soldiers includes the vast majority of them.

This fall, the Institute reached a milestone: The entire collection of Nanjing testimonies has been indexed and subtitled in English.

The collection could well be the world’s fullest audiovisual documentation of the rampage, which began during the Sino-Japanese War on Dec. 13, 1937, when Japanese troops arrived by horseback, tank and foot and embarked on a campaign of violence and rape that terrorized the city for several weeks.

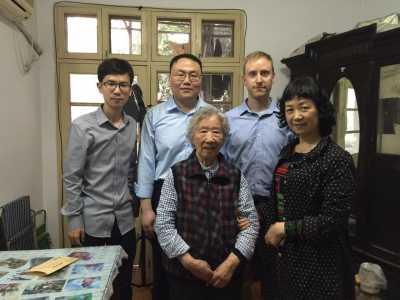

A key participant in the completion of the collection was Cheng Fang, whose deep involvement included tracking down survivors and their families in Chinese locations -- from villages to mega cities -- to record their life stories, as well as indexing the majority of the testimonies. The project was a partnership with the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall, a sprawling commemorative museum that provided crucial contact information and consultation.

Fang worked on the project for USC Shoah Foundation over a four-year period, and it became a big part of his life. He visited survivors on their death beds. He recorded the testimony of a well-known Japanese teacher who has researched the massacre at risk to her own personal safety. He even met his wife because of the project.

On Sept. 25, Fang indexed the final testimony.

“It’s kind of a relief, but also a bit sad,” he said, speaking via Skype from his home in China. “It’s a challenge to get testimonies and index them, but on the other side, it’s also very fulfilling.”

From 2015 to 2017, Fang and a crew that included camera and equipment operators and Karen Jungblut -- then the Institute’s director of collections and now its director of global initiatives -- made four tours through China. They recorded about 70 testimonies.

One of the most emotionally challenging interviews Fang conducted was with a 92-year-old woman who for many decades told journalists and researchers that Japanese soldiers had attempted to rape her several times. But it wasn’t until Fang interviewed her that she shared that one time, they succeeded.

“At one point she actually broke down and started crying,” he said.

When the woman grabbed his hand, and it became apparent that she was about to faint, he asked the camera to stop rolling for a while until she collected herself.

“I didn’t want her very traumatic image to be shown on the cameras,” he said, adding that in China, the shame and stigma associated with rape is especially severe.

The Nanjing collection includes an interview with Tamaki Matsuoka, a Japanese activist and former elementary school teacher who is widely known throughout China as the “Conscience of Japan.” Because her work has provoked death threats in Japan, she is careful never to publicize her home address.

After learning about the Nanjing Massacre as an adult, Matsuoka grew dismayed by its cursory treatment in Japanese textbooks.

“They tried to fudge the facts,” she says in her interview, conducted by Fang in 2016.

She decided to research the matter herself beginning in the late 1980s, and interviewed about 300 survivors and 250 ex-Japanese soldiers.

To find perpetrators, Matsuoka set up a hotline. Many called, but few admitted to committing atrocities themselves. In her testimony, Matsuoka mentioned one who did, Yoshiharu Matsuda. She said he initially wasn’t forthcoming, but opened up over the course of several interviews. He finally expressed remorse just before his death in 2004.

“(Matsuda) felt really sorry to Chinese citizens,” she said. “He told me that on his deathbed. There are many soldiers who haven’t reflected on their actions at all. But at least Mr. Matsumura changed his mind and had a guilty conscience.”

When he was indexing the testimonies from his home in China, Fang often came across obituaries for Nanjing survivors in the news. As a kind of tribute, he would start indexing that person’s testimony that day.

“I feel that I owe them something, I have to do something to show my homage,” he said. “For me it’s actually like a ritual, to mourn them.”

For a time, Fang worked in the office of USC Shoah Foundation in Los Angeles. One day, the collections department received an email from a researcher who was interested in being a part of the project. Jungblut forwarded the email to Fang, who arranged for the researcher to call for an interview. The researcher made no indication of gender in the email.

“Karen and I both somehow assumed automatically that it must be a guy,” Fang said. “So I actually pick up the phone and, OK, it’s a girl.”

Because Pingfan Zhang couldn’t get a visa, they didn’t hire her. But she and Fang continued to correspond. He later met her in person while on a trip in China collecting interviews. They married this year.

Fang said he is proud of the collection.

“First, as far as we know, this kind of interview hasn’t been done in China on such a scale,” he said. “Journalists and scholars, they just focus on the very short period of experience during the Nanjing Massacre, that’s it. But we did things differently. We are more interested in their whole life span – their whole life experience.”

In addition to preserving Chinese history, the project is a keepsake for the families, he said.

“It’s a family treasure to pass down to the next generations,” he said.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Forty of the Nanjing Massacre testimonies are available to anyone with an internet connection. All are subtitled in English. To find them, go to the Visual History Archive Online, and register for free. Then, on the left side of the screen, check the “Nanjing Massacre” box and, on the upper-center portion of the screen, click “search.”