What is propaganda? IWitness activity for Czech students explores 1968 Prague Spring

EDITOR’S NOTE: At a time when the term “fake news” has become pervasive – and when rising nationalism worldwide has had an especially pronounced effect on Central Europe – USC Shoah Foundation’s representatives in the Czech Republic, Poland and Hungary are introducing high school students to educational programs using a suite of new IWitness activities to provide a deeper understanding of propaganda.

This is the first of a three-part series that examines three new IWitness activities that delve into a major chapter of post-World War II history for each respective country: the Prague Spring of 1968 in former Czechoslovakia, the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, and the anti-Semitic campaign in Poland in March of 1968.

Propaganda and the Prague Spring

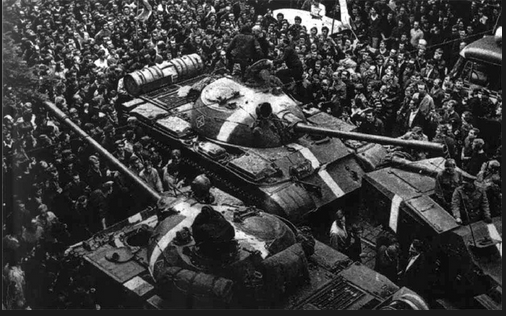

Fifty years ago, a silent revolution swept through Communist Czechoslovakia.

After ousting a hardline Stalinist president, the country’s new Communist leader, Alexander Dubcek, abolished government censorship and ushered in a free press. And thus began what is widely referred to as the Prague Spring. The attempt to create “socialism with a human face” wouldn’t remain bloodless for long.

The Czech-language IWitness activity “The Freedom of speech, censorship and propaganda in 1968 Czechoslovakia” exposes students in grades 9-12 to this landmark chapter of Czechoslak history.

“But the history is really a vehicle for analyzing propaganda and media manipulation,” said Martin Smok, USC Shoah Foundation’s regional consultant in the Czech Republic. “It’s really more about media literacy.”

The IWitness activity first examines classic Stalinist propaganda that reigned prior to 1968, such as forbidden books that had to be removed from all libraries and newsreels spreading falsehoods about the "American bug" that was sent across the border to eat the Socialist harvest.

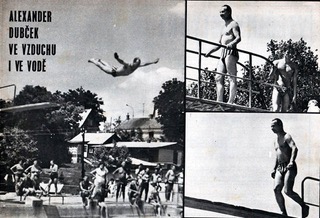

In the context of this environment, the Prague Spring was a shock to the sensibilities of ordinary Czechoslovakians. The sudden emergence of a free press exposed them to media content they hadn’t seen: the handsome Dubcek showcasing his physique in a bathing suit, political cartoons skewering dictators, the ability to publish essays and articles critical of communism and the Soviets. It also opened the gates for hate speech, much of which was antisemitic, and for calls for real democracy, not just a reform of the Communist regime.

A photo of Alexander Dubcek, the leader of the 1968 Prague Spring, in his bathing suit.

A photo of Alexander Dubcek, the leader of the 1968 Prague Spring, in his bathing suit. After reestablishing control, the Soviets installed a hardline regime and put censorship laws back in place.

In the activity, students watch a clip of USC Shoah Foundation’s testimony of Eduard Goldstucker, a literature professor who was thought to be the “spiritual father” of the Prague Spring.

“On my birthday, May 30, 1968, I received an anonymous letter,” Goldstucker says in his testimony. “Virulently antisemitic, which was to scare me, ‘You Jewish vermin,’ and so on, telling me that a report on my criminal activity was already sent to the Soviet Union.”

Goldstucker published one of the threatening letters with his commentary in a newspaper. When this move proved politically popular, his detractors accused him of writing the hate letter himself.

In the activity, students are prompted to think critically with several questions:

- Could freedom of speech be abused? How and by whom?

- Can you list two examples of such abuse of freedom of speech you have come across?

- Why do you think it was necessary for the regime to prohibit 11,470 books and have them destroyed?

The IWitness activity also touches on contemporary Russian propaganda about the events of 1968. It includes a clip from the 2015 Russian documentary “Warsaw Pact – Pages Declassified” that aired on state-run Russian TV, and falsely characterizes the Soviet invasion as a campaign to suppress a NATO-backed coup. Russian propaganda had also blamed the Prague Spring on Zionist conspirators. (The 2015 documentary marked a backwards step for the Russian government, which apologized for the invasion and 20 years of occupation in late 1989.)

“The result is a discussion,” Smok said. “What new information did the students learn, what are their differing interpretations of the events of 1968, what is the historical reality, what is propaganda, and what arguments do they have to back their assertions?”