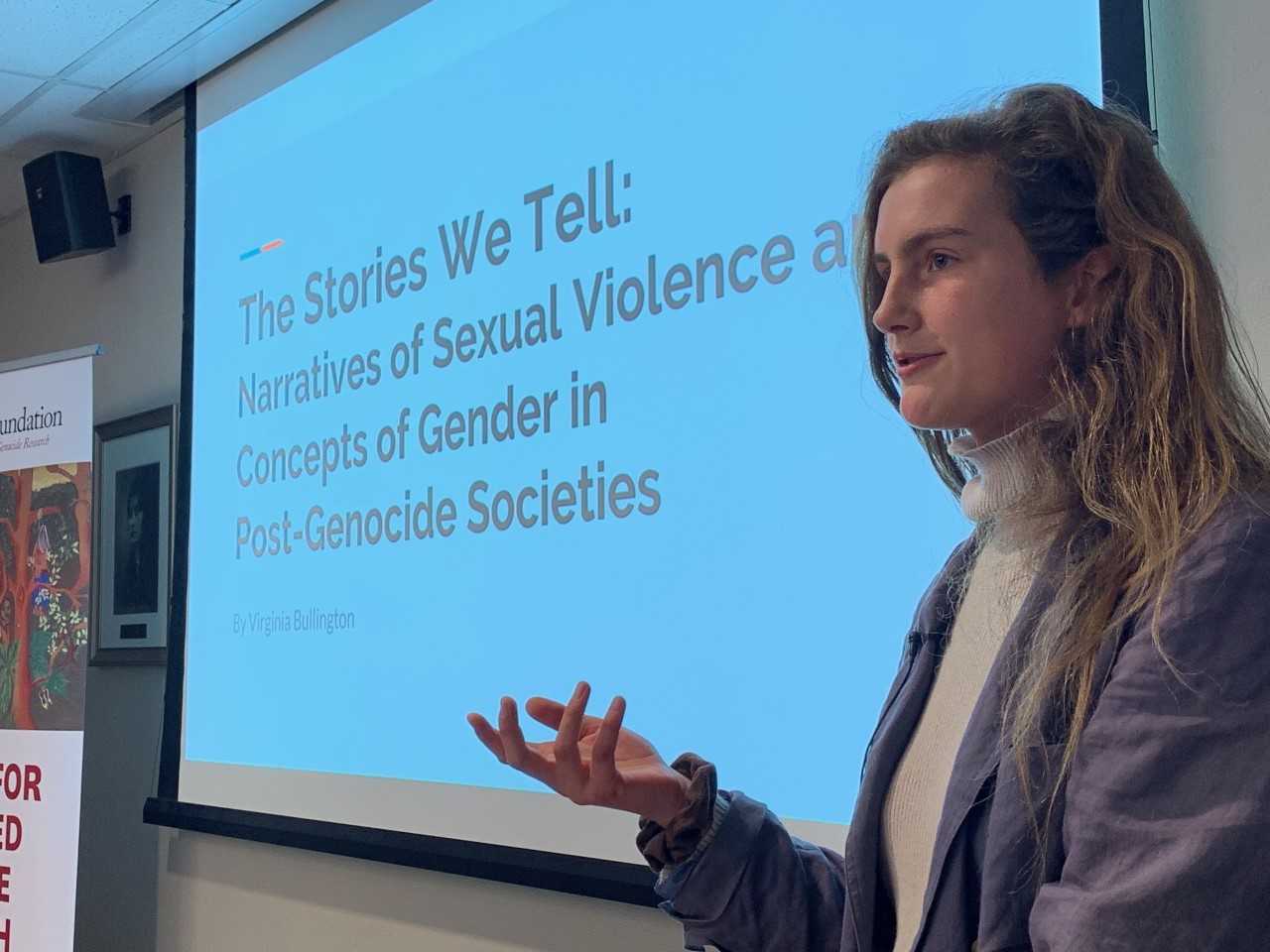

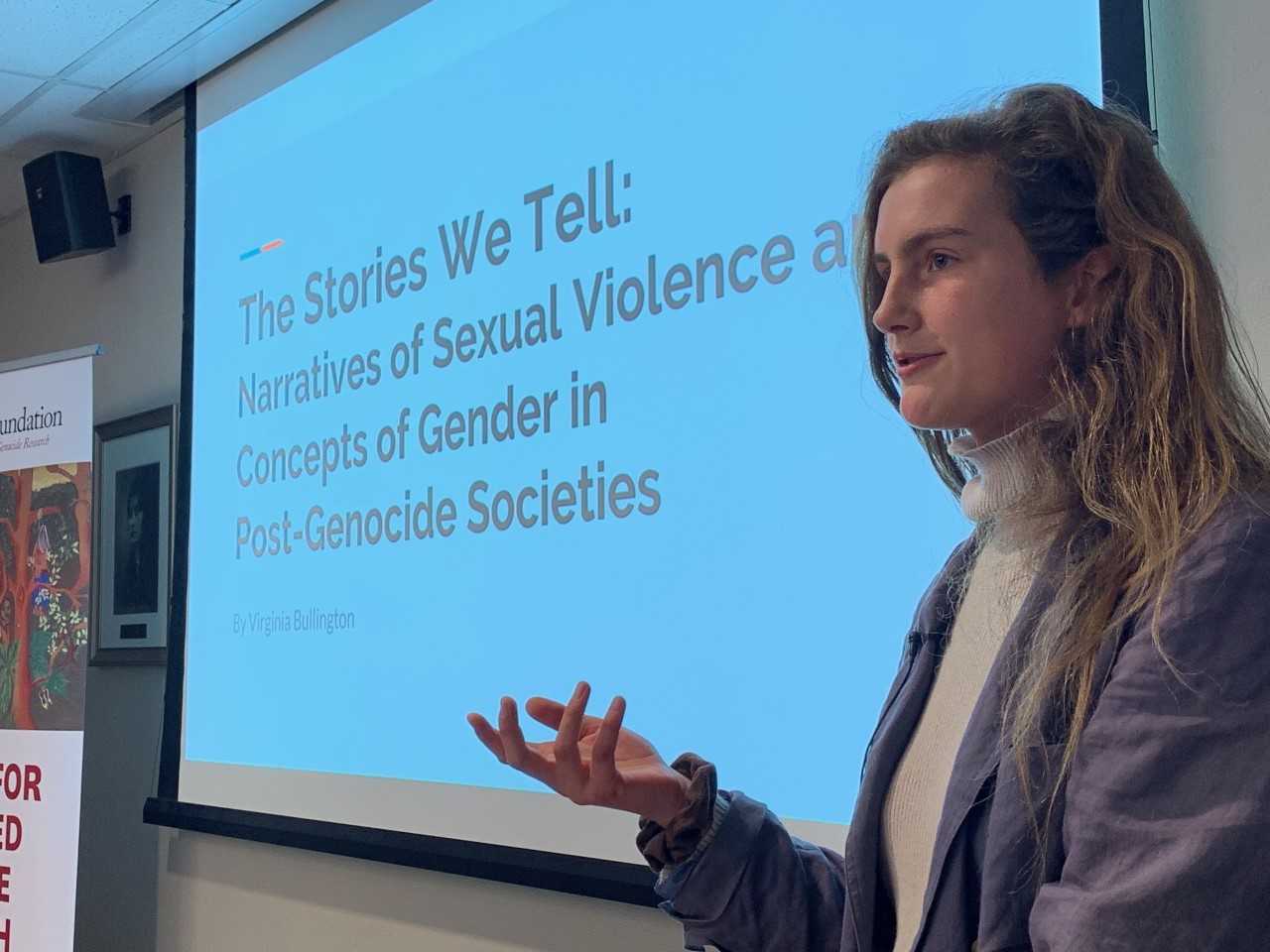

Lecture: Women victims of sexual violence during ethnic genocides often thought of as ‘vessels for nationalism’

Virginia Bullington

Virginia BullingtonAccording to an analysis by USC undergraduate student Virginia Bullington, the interaction – as described in Der Sarkissian’s testimony – typifies how Armenian women who survived the 1915 genocide are often talked about in the Armenian testimonies she observed: as vessels for nationalism, as opposed to individuals who suffered.

Bullington, who conducted her research at the Center for Advanced Genocide Research as the 2018 Beth and Arthur Lev Student Research Fellow, shared this and other observations in a USC lecture on Wednesday, Jan. 23 that compared the portrayal of women in three genocides: the Armenian, the Rwandan against the Tutsi (1994) and the Guatemalan against the indigenous population (early 1980s).

In the lecture, titled “The Stories We Tell: Narratives of Sexual Violence and Concepts of Gender in Post-Genocide Societies,” Bullington discussed the findings of her comparative analysis.

She found, among other things, that women in both Armenia and Rwanda are often described as “bearers of culture, maternity and nationalism,” while in the Guatemalan context, “indigenous women were not essentialized -- they were erased.”

A possible reason for this distinction: In the Armenian Genocide at the hands of the Ottoman Turks and the Genocide Against the Tutsi at the hands of the Hutu in Rwanda, the mass atrocities were characterized from the start in ethnic terms. The explicit goal was to eliminate the Armenians and the Tutsi as a people.

This stands in contrast to the Cold War-era Guatemalan Genocide, in which that country’s military targeted its indigenous Mayan population under the pretext of eliminating a Communist threat, she said.

To underscore her point, Bullington cited a quote from the late Efrain Rios Montt, the Guatemalan dictator who is said to have ordered many of the killings in 1982: “The guerrilla is the fish. The people are the sea. If you cannot catch the fish, you have to drain the sea.”

“While majority of the victims were indigenous civilians, they were treated as collateral damage rather than the real target of the massacres,” Bullington said.

Now in her third year studying narrative studies at USC, Bullington spent four weeks this summer as USC Shoah Foundation's Beth and Arthur Lev Fellow. She is currently working with the USC-UNESCO Journal for Global Humanities, Science & Ethical Inquiry to publish a paper based on the research she conducted using the Visual History Archive.

For many years, Bullington said, Mayan women felt too ashamed to speak about the sexual violence they suffered.

“This violence is explained away as politically necessary or an extracurricular for soldiers, therefore shameful,” she said. “Only recently – as this genocide is being recognized as ethnic rather than political – do women feel that their stories matter.”

She said the dominant narrative in Rwandan and Armenian cultures also seems to influence how people there often speak euphemistically about the rape that occurred during those genocides; often the term “marry” is used instead.

“This speaks to the idea that in raping or ‘marrying’ an Armenian or Tutsi woman, a Turkish or Hutu man can do double damage – both by stripping the ethnic identity of his victim,” she said, “but also by weakening the bloodline capability for her culture to progenate.”

The contemporary portrayal of women in the context of the Tutsi Rwanda genocide is sometimes over-simplified into a “whore/mother/angel” narrative – especially by men, Bullington said.

“Women were not just victims,” she said. “They were heroes, villains and bystanders. … They stand up to their husbands, they rescue, they escape.”

In the case of Rwanda, she found that men were more reticent than women to describe the details of sexual violence against women.

“Women, however, remember every name of every victim and perpetrator and say it loud and proud,” she said.

Despite how Bullington found that some Rwandan testimonies give short shrift to women as individuals, she noted that the country is actively working to resolve ethnic tensions.

She suspects this reckoning has helped put Rwanda in its current position as one of the world’s only countries with a parliament that is majority-female. Conversely, she suspects Guatemala’s failure to fully confront the true ethnic motives for its genocide plays a role in the country’s current struggles with gang violence and homicide.

“How these histories are told influences how these societies heal and move forward,” she said.