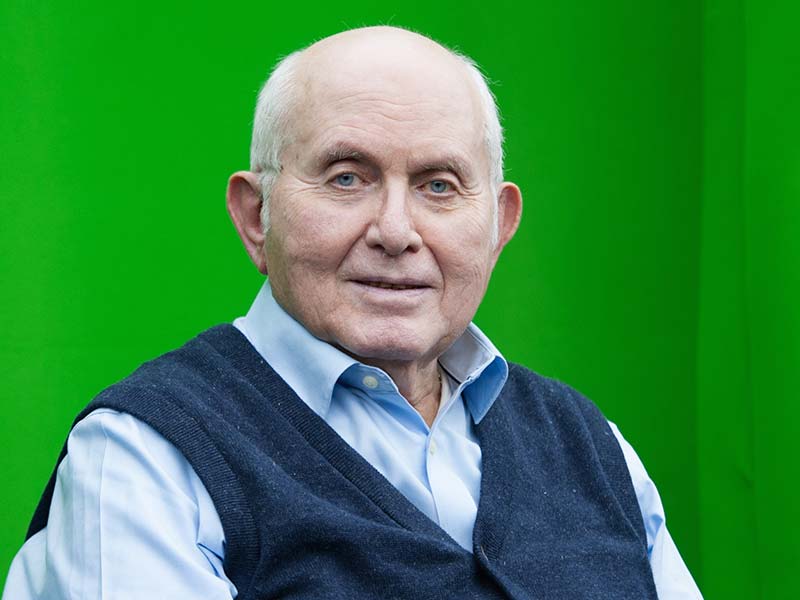

A Conversation with Pinchas Gutter

Pinchas Gutter is a survivor of six German Nazi concentration camps who now lives in Toronto, Canada. He has shared his remarkable story with USC Shoah Foundation in a variety of formats—through oral history in the Visual History Archive, as a Dimensions in Testimony interactive biography, in virtual reality and documentary film, and in person—and to commemorate Yom HaShoah, joined Interim Finci-Viterbi Executive Director Kori Street in a conversation on NPR's 1a.

We sat down with Pinchas to reflect on his experiences in honor of Yom HaShoah

When you were going through the very worst of what you experienced in the concentration camps, could you have ever imagined you’d be sitting here, talking about it, in the year 2022?

No. In the concentration camps you just existed. You didn’t think. You didn’t feel. When you are in the middle of a maelstrom of iniquity, or in a hurricane, the most important thing you can do is make yourself invisible.

So, during the Holocaust I was living in a cocoon, with blinders. I lived completely in the present moment, because at any second, any Nazi, any German, any Kapo, could do away with me. It didn’t mean anything to them. You were like a gnat that they could squash. So, you lived inside a cocoon and hoped that one the day the butterfly would come out.

Is it possible for anyone who didn’t live through the Holocaust to comprehend what you experienced?

This question comes up quite often, and I've always got the same answer: It’s not just impossible for people who didn’t experience the Holocaust to comprehend what happened. I myself am unable to comprehend what happened. I have no idea.

The fact is that what happened in the Shoah is incomprehensible. Incomprehensible to you, and incomprehensible to me.

“You lived inside a cocoon and hoped that one the day the butterfly would come out” —Pinchas Gutter

How has your experience as a survivor influenced your life?

There is this anxiety that doesn't leave you. The Holocaust is inside you forever. And there’s nothing you can do about it. You went to a school called Shoah.

My love for my family, I experience it in terms of fear. For instance, my wife goes to have tea with her friends and says she’ll be back at five. And at six I start worrying. Why should I start worrying? It’s just a normal day. But I start worrying because this is how I experience love for people. This is how I relate to the world.

When I look at a vase of flowers, I know they are nice. But my wife reacts to them differently, with a kind of emotion that I lack. Because on the death march the only thing you could do with a flower was try and eat it, because that’s what kept you alive.

How were you able to cope in the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust?

The brain is a funny thing, it does all kinds of things to make you be able to function, to go on. For the first 10 years after the war, I never gave even one minute of thought to the Holocaust. Nothing. It was only 10 years after I was liberated that I started having nightmares.

What helps in general is being able to see the happiness of others. When you do, you see that it's possible to be happy in your own life. And looking into the soul of others—and seeing how much goodness there is among ordinary human beings—it allows you to exist, allows you to come to terms with things.

You’ve taken groups on trips to concentration camps. You speak to students around the world. You were the first Holocaust survivor to participate in USC Shoah Foundation’s Dimensions in Testimony program. What motivates you?

You know how the Olympic torch has one flame? Well, I have a something I call the “Torch of Goodwill” that has a lot of flames. The first flame is no racial discrimination. The second is no religious discrimination. The third is no xenophobia, no homophobia, and no hate. Hate is pernicious. Hate is vicious. It should be banished from the heart. And I say to my audiences: “This torch is my gift to you. Use these flames and hand them over to others to brighten up the world. Make the world a brighter place."

I do these things because I want to tell people what happened, and I want them to understand what is happening now. For young people, I want them to grow up to make sure that things like the Holocaust do not happen again.