As the Nazis assumed power in Germany in 1933, many artists and intellectuals opposed to the regime sought refuge in Latin America, particularly in Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico.

Raíssa Alonso, a PhD Candidate in Social History at the University of Sao Paulo, was awarded the 2022-2023 Margee and Douglas Greenberg Research Fellowship at the USC Dornsife Center for Advanced Genocide Research (CAGR). Earlier this year, she spent a month at the Center exploring testimonies in the Visual History Archive related to the anti-Nazi resistance movements the German diaspora formed while in exile.

“Raíssa Alonso is conducting groundbreaking research,” said Wolf Gruner, Founding Director of CAGR. “Her discoveries in the testimonies and other unique archival materials at USC Libraries' Special Collections bring to light a wide range of resistance activities and networks between Brazil, Argentina, and the United States. Her work is redefining what we know about anti-Nazi resistance in Latin America.”

In late March Alonso gave a lecture and sat for an interview to discuss her findings.

Roughly how many artists and intellectuals sought refuge in Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico after the Nazis came to power?

It’s hard to say the exact number, but we do have general figures about German immigration to the American continent during this period. The US received over 130,000 German refugees during World War Two, and Argentina, Brazil and Mexico took in significant numbers as well. Argentina received approximately 45,000 German refugees, the majority of whom settled in Buenos Aires. In Brazil, researchers estimate that some 33,000 German refugees were welcomed between 1933-1945, which amounted to about 30 percent of the German-Brazilian community at the time. And there are estimates that Mexico received around 22,000 German refugees between 1930-1950.

What did the anti-Nazi resistance movements in those countries look like? What are the concepts that united them?

A dream shared by all anti-Nazi groups on the American continent was the creation of a united front to fight Nazism involving people from across the political spectrum.

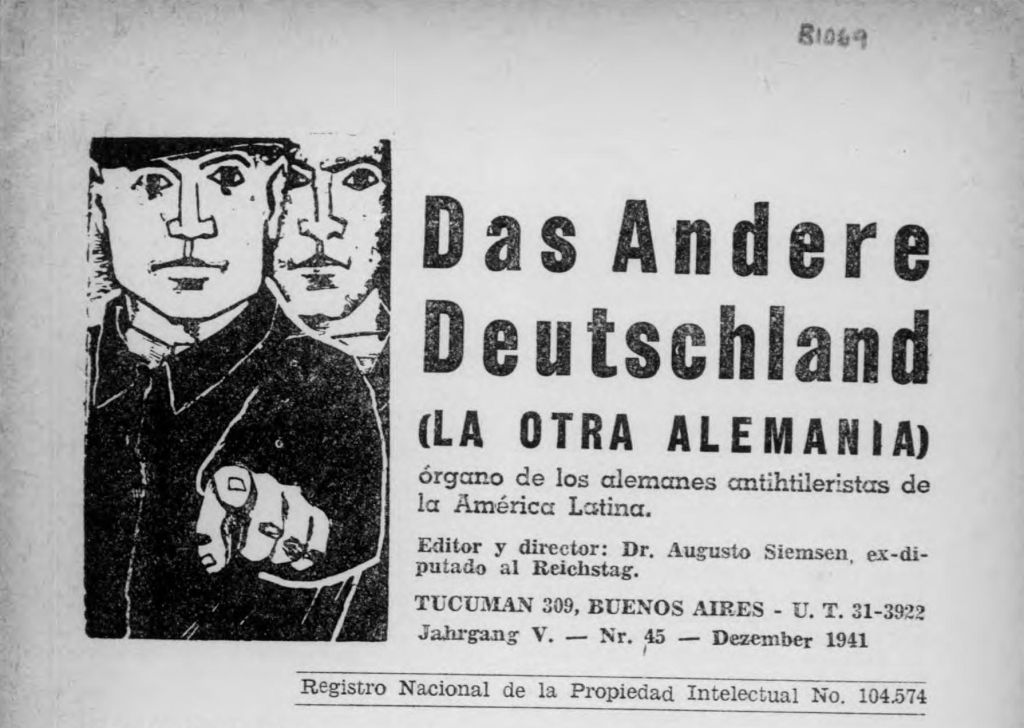

Several anti-Nazi resistance movements were founded in Latin America, such as Das Andere Deutschland in Argentina, Movimento dos Alemães Livres in Brazil and Freies Deutschland in Mexico.

Many of these movements revolved around the concept of “Das Andere Deutschland” (“The Other Germany”), the idea that Hitler’s Third Reich didn’t embody the true morals and ideals of Germany, the most important of which was its humanist tradition. Under the umbrella of The Other Germany, it was possible to find all manner of political affiliations, including liberal, monarchist, anarchist, communist, democratic, and even totalitarian—in short, anything that opposed Nazism.

The groups organized study sessions, reading circles, published newspapers and organized fundraisers for the war effort, even going as far as volunteering to fight alongside armed forces on the European battlefront.

What were the divergences that made the dream of a united resistance front impossible?

The Other Germany concept was a way to explore two main questions, one pertaining to the nation’s past and the other its future. In newspapers, articles, pamphlets, manifestos, German-speaking authors and intellectuals debated the reasons for Germany’s fall to fascism.

While there may have been some measure of agreement on the causes of the “problem of the German soul”, it is safe to say that the main divisive issues related to differing views on Germany’s future. Some thought that a post-war Germany should reclaim its former glory, either by joining a dreamed post-war European federation or by establishing a strong modern economy. Others hoped for a communist revolution, citing the material conditions that would be present in a post-war Germany. And there were others who simply wanted a complete restoration of democratic Germany, and others who even considered a return to monarchy as the best path for their nation.

But the union of all political currents proved to be irreconcilable, with both the Argentinean and the Mexican groups rising stronger than their counterparts. The Latin American movements ended up being forcibly disbanded after the end of the war, when a good number of exiled intellectuals returned to Europe. Expectations were shattered by the reality of post-war Germany, and while many chose to stay in Latin America, the last movements would peter out by the early 1950’s.

What did you find in the Visual History Archive?

Up until now, most of my primary sources have been newspapers, manifestos and police records, so it's completely different to hear survivors in their own voices. The Visual History Archive gave me the opportunity to hear about individual resistance in the German communities of Argentina, Brazil and Mexico. Some of the testimonials also shed light on obscure parts of these movements’ histories.

For instance, I learned a lot from the testimony of Heinz Geggel, the Secretary of Freies Deutschland in Cuba, one of the largely forgotten chapters of the anti-Nazi resistance movement. Geggel also mentions the existence of several other anti-Nazi movements across the continent, and speaks about what he learned when he entered the movement and the questions he started to ask himself once he had joined. It’s interesting because we know next to nothing about what was happening in Cuba at that time. We know that [the movement] had a presence there, but this was the first time I actually came across anyone mentioning it in any detail. So his testimony sheds light into a previously unknown part of the subject.

There are other testimonies that shed light on the less-known resistance movements in the region. For example, there’s the testimony of Stephen Kalmar, who arrived in Mexico with his pregnant wife in 1940. In his testimony, Kalmar says his wife was almost due to give birth and that the couple had no plan for the delivery. Someone recommended that they see Dr. Ernest Frank, who was also at the time president of the Menora movement. And Dr. Frank not only delivered their baby, but he then organized a care package for the newborn and had it sent to their house.

[The testimony gives] such a human dimension to Dr. Frank. I’ve read about how he was a fierce defender of human rights, but it's different to hear about his actions, how he actually helped people. In Kalmar’s testimony, Dr. Frank is spoken of with such sweetness, such tenderness, that it's impossible not to humanize him a little more.