Under the shadow of Paragraph 175: Part 1: Albrecht Becker

The Holocaust collection in USC Shoah Foundation's Visual History Archive contains over 57,466 testimonies; however, only a mere six of those testimonies are from survivors who were persecuted by the Nazis for being gay: one in English, three in German, one in French, and one in Dutch. There are other gay survivors we have in the Archive, but they were persecuted by the Nazis for the greater sin of being Jewish; Gad Beck being one of them. The meager number says a lot about the history of the gay men who lived through the Nazi regime and who came out the other end willing and unafraid to speak about their lives.

It is easy to forget that their persecution did not end with the war in 1945. Paragraph 175, the German code outlawing homosexual acts between men had been on the books since 1871 and, though considerably limited in its enforcement by 1969, would not be completely revoked until 1994 when Germany reunified. Many of the men tried under Paragraph 175 during the war still were made to serve out their sentences after the war. It is not without irony that the new West German government would retain the Nazi's more oppressive revision of the law rather than reverting to the more lenient version on the books before the war. East Germany, on the other hand, actually removed the Nazi amendations to the law.

This blog post is my attempt to bring their stories to the surface, focusing on each of the men whose testimonies I can personally watch and respond to. This post will focus on the life of Albrecht Becker. Unfortunately, I do not know Dutch or French, so the stories of Pierre Seel and Tiemon Hofman continue to remain a mystery to me, still buried. I hope that someone will eventually discover them in the Archive and share their stories with us.

Albrecht Becker

Albrecht Becker gave us his testimony in 1997 at the remarkable age of 91. Born in 1906, in the town of Thale, Becker was a baker's son, who remembers as a child delivering bread to the restaurants and hotels in his pull wagon. The youngest of three sons, Becker remembers once as a child overhearing his teachers mentioning that they did not think that he was as smart as his older brothers, an episode that affected his self esteem throughout his life. As a child, he was not very interested in sports, preferring to play with dolls and pursuing needlework and knitting. His father, a practical man, decided to steer his son's interests toward a career in textiles, to which Albrecht did not entirely object. He entered an apprenticeship to study the trade and after graduation at the age of 18 moved to Würzburg.

In Würzburg, away from his family, Becker was able to live more freely as a gay man. He began his first long-term relationship with Joseph Arbert, a professor who was more than twenty years his senior. The older man became Becker's intellectual mentor, introducing him to a world of art and literature. They would remain together until the Gestapo arrested them ten years later in 1935.

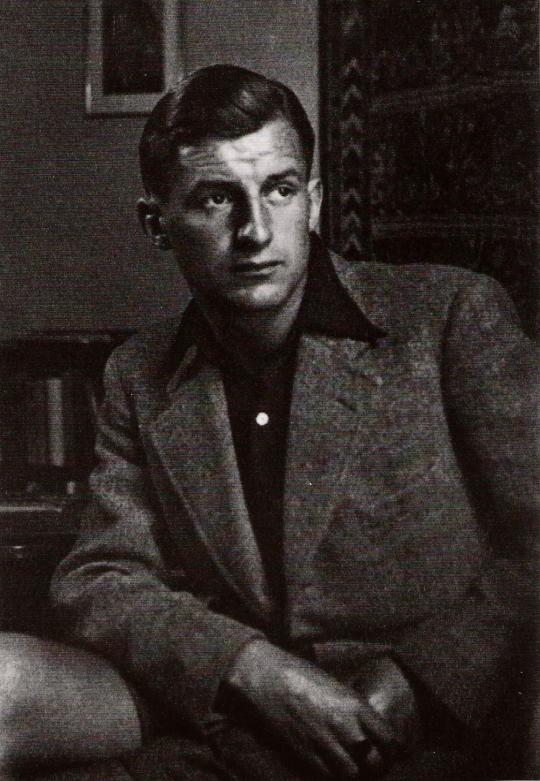

Albrecht Becker with Wenderer Brown in Italy, 1926

Albrecht Becker with Wenderer Brown in Italy, 1926Ironically, after a month-long visit with Brown in the United States in August of 1934, Becker misses Würzburg too much to stay and returns to Germany, unaware that he would be arrested three months later for violating Paragraph 175. Had he known, he would have stayed safely ensconced in America, but, as Becker notes, his desire to return to Nazi Germany was a sign of how safe gay men felt during that time. This feeling of relative security despite Paragraph 175 was largely due to the well-known fact that the commander of the SA, Ernst Röhm, was gay. The reasoning was that if Röhm could be openly gay as a Nazi commander, then gays in Germany should have have no problem living openly themselves. However, the Night of Long Knives in June 1934 would change all of that. The internal power struggle between Röhm with his growing SA army and Hitler, beholden to the Reichswehr, culminated in the murder of hundreds of political enemies, including Röhm, in the span of a few days. The aftermath of the Putsch was the consolidation of Hitler's power as "supreme leader" and a very dangerous environment for gays living in Nazi Germany.

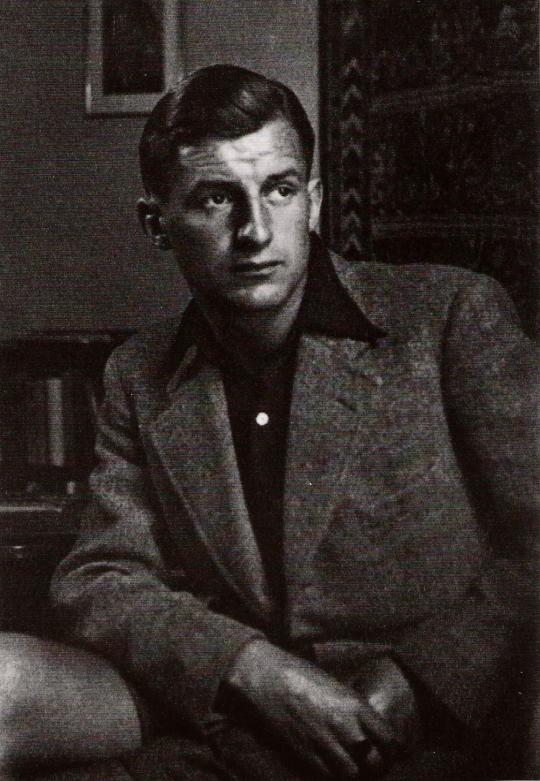

Albrecht Becker, after the warBecker's arrest and incarceration

Albrecht Becker, after the warBecker's arrest and incarceration

Albrecht Becker, after the war

Albrecht Becker, after the warAfter the June 1934 Putsch, things remained quiet in Germany that summer. Becker was able to freely leave the country to visit Wenderer Brown in Texas. After his return, the situation for gays continued to remain quiet throughout the rest of the year until the beginning of 1935, when Albrecht Becker received a summons to appear at the police station for questioning. The officer, a well-dressed man by the name of Gerun, asked Becker if it was true that he was a homosexual. "Of course," he recalls responding, "everyone in Hamburg knows I'm gay." During the interview, he inadvertently incriminated Dr. Arbert, whom the Gestapo will arrest the next day. Becker was held in custody for three months until his trial. At the trial, he did not contest the charges, which ended up saving his life ironically. He was found guilty and sentenced to prison for three years in Nuremberg. The others on trial who denied the charges ended up getting sent to Dachau concentration camp, where they were never heard from again. When asked if he had any regrets or animosity about the whole ordeal, Becker is matter-of-fact. He knew he was breaking the law and was prepared to pay the price, or as he says, "swallow my medicine." After serving his time in Nuremberg, Becker returns to Würzburg and his former life with his friends and family. He is even able to go back to work at the department store despite the public knowledge of why he was incarcerated.

Listening to his testimony, I find it very surprising to hear the resignation in his voice about what I see as a great injustice. No anger or sadness; just a shrug of indifference. He knew his actions were illegal, he did them anyway, he got caught, and he was willing to take his lumps. Also shocking is learning that he will eventually volunteer to serve in the war. He is not motivated by patriotism or any allegiance to the Nazi party, however, but simply because there are no more men left in town. He craves the company of men. The interviewer asks him if there is any erotic component to his life in the military. Becker immediately dismisses the notion. The risk of being caught in the military is too high. It would mean being sent to a concentration camp at best; execution at worst. For Becker, he merely wanted to be where the men were. That eventually meant being shipped to the Russian Front, where he worked with the radio corps, which actually kept him from seeing any action since he always needed to remain ten kilometers behind the front line. His superiors encouraged him with his photography so he took advantage of his time to take several photos there.

Post-war

As it became evident that the Nazis were losing the war, his division began its long, arduous retreat. After being in no danger on the Russian Front, it is ironically on their retreat through Ukraine that Becker was injured in an air raid, hit by shrapnel in his right arm, effectively ending the war for him. He is eventually transfered to Vienna and from there makes his way back into Germany where he meets American forces who enlist him as a translator at a train station. They release him in 1947, and he then gets a call from a filmmaker, Herbert Kirchhoff, that changes the direction of his life forever.

Becker's post-war life is a very creative period. Kirchhoff and he relocate to Hamburg and, from there, they collaborate on several films. Becker's role as set designer on their films gives him a foothold in the industry allowing him to work on other independent projects, including theater and opera. Among his many film projects are "Toxi" (52), "Keine Angst vor grossen Tieren" (53), "Des Teufels General" (55), "Zwei blaue Augen" (55), "Der Hauptmann von Köpenick" (56), "Die Zürcher Verlobung" (57), "Monpti" (57), "Nasser Asphalt" (58), "Der Schinderhannes" (58) and "Die schöne Lügnerin" (59). He also continues his love for photography and eventually publishes his memoir Fotos sind mein Leben (Photos Are My Life).

Starting in his 40s, Becker also becomes his own work of art, using his body as a canvas for tattoos that will eventually cover his entire body below his neck. If you pay attention to his testimony clips, you will see his tattoos peeking out from under his arm sleeve. They are fascinating to see on an otherwise dapper, soft-spoken gentleman. I wish the interviewer would have asked him about the history behind the tattoos. What made you get your first tattoo? What does it represent? What made you continue to cover the rest of your body? They punctuate an astonishing life uninterested in hiding in the closet.

As remarkable as Albrecht Becker's testimony is as a snapshot of one gay man's confrontation with a homophobic regime, it is sad to remember that his is not the only one, not just of those who survived the Holocaust but of those who must face state-sanctioned homophobia today in such places as Russia, Uganda, Indonesia, and lands occupied by ISIS, where gay men are summarily hanged under the guise of religion. Even here in the United States we see exerted attempt to institutionalize homophobia, the "religious freedom" act passed and signed into law in Indiana is just a recent instance. In this same year, we have seen a ballot initiative proposed in California that would make homosexuality punishable by death, and a judge in Texas blocked implementation of a Federal Government order that would have extended family and medical leave benefits to same-sex couples. Perhaps Albrecht Becker would not have faired any better had he remained in Texas.

Albrecht Becker was 95 when he passed away on April 22, 2002, in Hamburg, Germany. His private photo collection is now housed at the Schwules Museum in Berlin.