Remembering Dr. Ruth Westheimer

The USC Shoah Foundation mourns the loss of Dr. Ruth K. Westheimer, a Holocaust survivor who fled Nazi Germany without her parents at the age of 10 and went on to become a renowned and beloved sex therapist and media personality. She was 96 years old.

Known for her 4’7’’ stature, matter-of-fact attitudes toward sex and sexuality and her German-accented catchphrase “get some!,” Dr. Ruth revolutionized the way Americans spoke about sex, opening up candid and often humorous discussions of taboo topics.

Dr. Ruth recorded her testimony with the USC Shoah Foundation in 1998, at age 70. (Watch her full testimony.) In 2020, the USC Shoah Foundation, along with Delirio Films and Neko Productions, produced Ruth: A Little Girl’s Big Journey, an animated short about Ruth’s early life as a refugee that is used as a teaching tool in primary grade classrooms. Ruth has also been featured in multiple USC Shoah Foundation IWitness educational activities about courage, identity, and family stories.

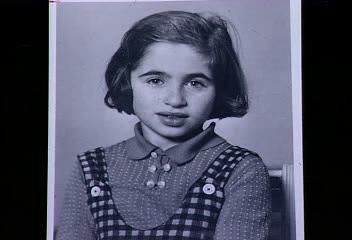

Karola Ruth Siegel was born on June 4, 1928, to Orthodox parents in Frankfurt, Germany. As an only child, she recalled being “very well cared for” and even spoiled at times—she had 13 dolls and a pair of rollerskates. She spent summers visiting her maternal grandparents in Wiesenfeld.

Her mother, Irma Siegel, worked as a housekeeper, and her father, Julius Siegel, was a wholesaler. In Ruth’s testimony, she remembered studying with her father as he took her to school on his bicycle and attending synagogue with him every Friday night. He always kept exact change in his vest pocket to buy her ice cream on the way to synagogue. Later Ruth would reflect on her happy childhood, saying “early socialization was crucial in my whole joie de vivre, my lust for life, despite the unhappy occurrences.”

Ruth retained only passing memories of the November Pogroms, also known as Kristallnatch, when the Nazi party unleashed an organized assault on the Jewish population in Germany, Austria, and the Czech Sudetenland on November 9 and 10, 1938.

But she clearly remembers when her father was arrested soon after.

Nazis banged on the door of the Siegel home and demanded her father get dressed. Ruth cried as her grandmother handed the Nazi officers money from the hem of her skirt to keep her son safe. She watched her father wave and wink at her as he stepped into the covered truck, which would take him to Dachau concentration camp. “I remember that wink and I thought, you know, he’s going to come back,” Ruth said in her testimony.

Ruth, then 10, was told that she would be sent to Switzerland for six months and that her father’s release depended on her leaving. On January 5, 1939, Ruth joined 100 other children on a train to Wartheim, a Jewish Orthodox children’s home in Heiden, Switzerland. Ruth remembered her mother and grandmother running to say goodbye and watching the train pull out.

That was the last time she saw her family.

Between December 1938 and September 1939, as Nazi persecution of Jews escalated, some 10,000 Jewish children were sent from Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia to safety, mostly in Great Britain, in what became known as the Kindertransport. Ruth was on a similar transport to Switzerland.

After a few months, Ruth’s father returned home to Frankfurt. She received letters from him in the form of poems to avoid censors, along with letters from her mother and grandmother, reminding her to “remain a good girl” and “trust in God.”

The Second World War was ignited when Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, but Ruth recalled not knowing much about the war while at Wartheim. In 1941, the letters from her family ceased. Her six-month stay would turn into six years.

“They kept a roof over my head and fed me for six years,” Ruth acknowledged in her testimony. But her time at Wartheim was far from simple. Looking back, she remembered the “overwhelming feeling” of being told to be grateful and never complain. The home was run by refugees from Berlin. Ruth later wondered why the staff told the children that their parents were wrong for sending them, “instead of recognizing their sacrifice.”

She and other refugee children looked after the home’s paying Swiss children, doing laundry and ironing. While boys were able to attend high school, girls could only train to be housemaids. Eager to learn, Ruth borrowed her boyfriend’s schoolbooks and read them at night, studying history and mathematics under the staircase light.

Ruth prayed, learned a bit of Hebrew, kept kosher, and observed Shabbat at Wartheim. She studied Zionism and when young Jewish emissaries arrived from Palestine to Wartheim, she decided she would be on the first boat to British Mandate Palestine. In 1945, she got that chance, boarding a ship leaving from Marseilles.

There was “excitement in the air” as Ruth traveled to Palestine, seeing the ocean for the first time. However, she worried about traveling further from her home and perhaps her family, who she hadn’t heard from in nearly four years.

“How do I leave Europe without knowing where my parents were? How are they going to find me if they ever come back?” she recalled thinking.

In Palestine, she switched her first and middle names, becoming Ruth Siegel, keeping Karola as her middle name in case her parents came looking for her. Later in her life, Ruth would find out that her father, paternal grandmother, and maternal grandparents were sent to Theresienstadt and Auschwitz concentration camps and killed. Her mother was marked as verschollen, which meant “disappeared.”

Ruth settled in Kibbutz Nahalal in the country’s north, where she worked picking tomatoes and olives, then moved to Kibbutz Yagur on Mount Carmel, where she arranged to study in a seminary for kindergarten teachers in Jerusalem. She then became a member of the Haganah, Israel’s nascent defense force, where she trained to be a sniper, learning how to throw hand grenades and put together a STEN gun with her eyes closed.

On Ruth’s 20th birthday in the summer of 1948, during the war that followed the establishment of the state of Israel, she was headed to a shelter after hearing sirens when a cannonball shot through the wall, killing two women next to her. Shrapnel penetrated her legs, nearly costing her her feet.

In 1950, she married David Bar-Haim and traveled to Paris where he began medical school. She entered the Sorbonne to study psychology, which she described as a “fantastic opportunity.” David eventually gave up his studies and returned to Israel, but Ruth stayed in Paris to continue studying with a group of Israeli friends and the marriage ended. During this time, she did not speak of the orphanage or the Holocaust.

“It was too soon, even 10 years later, too raw—distance was important to live a full life.”

In 1956, she received a check from the German government for 5,000 marks, sent to everyone forced to stop their schooling during the war. The same year, she came to New York City with a Frenchman, Dan Bommer, whom she married and had her first child, Miriam, named in honor of her mother Irma. She rented a room in Washington Heights and got a scholarship to the New School for Social Research to study sociology. She and Dan divorced a year later and she and Miriam stayed in Washington Heights, a German-Jewish neighborhood where she felt she fit in, and where she would live for the rest of her life.

Ruth focused her master’s thesis on the refugee children who had left Germany in 1939, and the importance of early socialization.

“Psychologically it helped me to keep part of the past alive while being in a brand new language, a brand new environment, a brand new country,” she said about working on her thesis.

She met her husband, Fred Westheimer, in 1960 and they married a year later. They had their son Joel in 1963 and Fred adopted Miriam.

Ruth went on to work in research at Planned Parenthood in 1967. “These people were crazy. They only talk about sex, not the weather, not literature,” she said in her testimony. But she found it very intriguing. She received her doctorate in interdisciplinary study of the family and started to teach at Lehman College in 1970.

Ruth was accepted into a sexuality program at Cornell Medical School where she studied to be a sex therapist under Dr. Helen Singer-Kaplan. In 1981, she appeared on WYNY radio station giving sex and relationship advice under a mandate to cover community issues. The segment was so popular she earned her own weekly show, Sexually Speaking. Soon after, “Dr. Ruth” quickly shot into stardom, appearing in commercials, movies, and even a talk show.

At the height of her career in the 1980s and ‘90s, Ruth spoke about sexuality like no one had before, drawing from her life and past experiences to make an impact. She showed support for the gay community during the AIDS epidemic, later saying in Ask Dr. Ruth, a 2019 Hulu documentary, that “because of my background, I had a sensitivity to people that were treated as subhuman.” She connected her Jewish faith and culture to sexuality in her book Heavenly Sex: Sexuality in the Jewish Tradition and expanded her audience with her other books Sex After 50, Sex for Dummies and Dr. Ruth Talks to Kids.

Fred died in 1997, and Dr. Ruth continued to educate by speaking, lecturing, and publishing books well into her 90s. Ruth concluded her USC Shoah Foundation testimony by proudly showing photographs of her life and family—from portraits of her parents to smiling baby photos of her grandchildren.

“I have a strong feeling that Hitler and all of the Nazis did not want me to have grandchildren. So that’s an overriding, very strong feeling of triumph…of saying, you see? With all the sadness, there is nobody that has grandchildren like mine.”

Ruth is survived by her children, Miriam and Joel, and her four grandchildren.