Andy Friendly

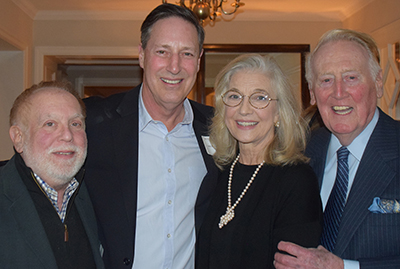

Left: Evening to Benefit USC Shoah Foundation co-hosts Ken Ehrlich, Andy Friendly, and Sandra & Vin Scully

Inspired by last year’s historic Auschwitz: The Past is Present program, producer Andy Friendly is taking his tradition of remembrance to heart by joining the USC Shoah Foundation Board of Councilors.

Friendly, a graduate of the USC School of Cinematic Arts, has produced shows including Entertainment Tonight and The Tomorrow Show on NBC, and was president of programming and production at King World/CBS from 1995 to 2001. He continues to produce through his company Andy Friendly Productions.

Friendly has a longtime tradition of watching Schindler’s List every year with his close friend David Zaslav, president and CEO of Discovery Communications. Earlier this year, Zaslav told him about USC Shoah Foundation and Discovery’s involvement in the Auschwitz: The Past is Present program, which commemorated the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz in January.

Friendly said he has always admired the work of USC Shoah Foundation, but after he heard about Auschwitz: The Past is Present, visited the Institute and met its leadership, he was motivated to get involved himself.

“I’m trying to spend whatever time I have left on this planet to create awareness of important causes, and I can’t imagine any cause or issue that’s more important than keeping alive the memory and the history of the survivors of the Holocaust, and past and current genocides around the world,” Friendly said. “I look forward to playing a small role and doing whatever I can to further the mission of the foundation.”

Friendly hosted his first donor event on February 1 to introduce his friends and colleagues to USC Shoah Foundation and share some of its recent projects and achievements.

Friendly has a personal connection of his own to the Holocaust. His father Fred Friendly, before he was a celebrated CBS News journalist was a sergeant in the Army during World War II – and a witness to the liberation of the Mauthausen concentration camp.

In an extraordinary letter to his mother written May 9, 1945, Fred Friendly recounts the horrors that he saw at Mauthausen. At the end of the letter, he encourages his family to share his story with their friends and neighbors, and to read the letter to their grandchildren every Yom Kippur. Friendly said he has indeed continued this tradition with his family.

Given his family history, Friendly is particularly interested in sharing the stories of liberators. Though his father spoke often about his experiences during World War II while Andy and his siblings were growing up, there are very few people left who have access to eyewitnesses, so the work of USC Shoah Foundation is very important, he said.

“The liberators’ story is a story that should be told as well as the survivors’ stories. It is so important to keep these memories alive,” he said. “I think these stories of the liberators as well as the survivors are meaningful, very emotional and will have an important impact on our kids and grandkids and future generations.”

Fred Friendly’s Mauthausen letter

Paris, France

May 10, 1945

Dear Mother,

In just a few days I will be in an airplane on my way back to the APO to which you write me. Before I leave Europe, I must write this letter and attempt to convey to you that which I saw, felt and gasped at as I saw a war and a frightened peace stagger into a perilous existence. I have seen a dead Germany. If it is not dead it is certainly ruptured beyond repair. I have seen the beer hall where the era of the inferno and hate began and as I stood there in the damp moist hall where Nazidom was spawned, I heard only the dripping of a bullet-pierced beer barrel and the ticking of a clock which had already run out the time of the bastard who made the Munich beer hall a landmark. I saw the retching vomiting of the stone and mortar which had once been listed on maps as Nurnheim, Regensberg, Munich, Frankfurt, Augusburg, Lintz, and wondered how a civilization could ever again spring from cities so utterly removed from the face of the earth by weapons the enemy taught us to use at Coventry and Canterbury. I have met the German, have examined the storm trooper, his wife and his heritage of hate, and I have learned to hate - almost with as much fury as the G.I. who saw his buddy killed at the Bulge, almost as much as the Pole from Bridgeport who lost 100 pounds at Mauthausen, Austria. I have learned now and only now that this war had to be fought. I wish I might have done more. I envy with a bottomless spirit the American soldier who may tell his grandchildren that with his hands he killed Germans.

That which is in my heart now I want you and those dear to us know and yet I find myself completely incapable of putting it into letter form. I think if I could sit down in our living room or the den at 11 President, I might be able to convey a portion of the dismal, horrible and yet titanic mural which is Europe today. Unfortunately, I won’t be able to do that for months or maybe a year, and by then the passing of time may dim the memory. Some of the senses will live just so long as I do - some of the sounds, like the dripping beer, like the firing of a Russian tommy gun, will always bring back the thought of something I may try to forget, but never will be able to do.

For example, when I go to the Boston Symphony, when I hear waves of applause, no matter what the music is, I shall be traveling back to a town near Lintz where I heard applause unequalled in history, and where I was allowed to see the ordeal which our fellow brothers and sisters of the human race have endured. To me Poland is no longer the place where Chopin composed, or where a radio station held out for three weeks - to me Poland is a place from which the prisoners of Mauthausen came. When I think of the Czechs, I will think of those who were butchered here, and that goes for the Jews, the Russians, Austrians, the people of 15 different lands, - yes, even the Germans who passed through this Willow Run of death. This was Mauthausen. I want you to remember the word... I want you to know, I want you to never forget or let our disbelieving friends forget, that your flesh and blood saw this. This was no movie. No printed page. Your son saw this with his own eyes and in doing this aged 10 years.

Mauthausen was built with a half-million rocks which 150,000 prisoners - 18,000 was the capacity - carried up on their backs from a quarry 800 feet below. They carried it up steps so steep that a Captain and I walked it once and were winded, without a load. They carried granite and made 8 trips a day... and if they stumbled, the S.S. men pushed them into the quarry. There are 285 steps, covered with blood. They called it the steps of death. I saw the shower room (twice or three times the size of our bathroom), a chamber lined with tile and topped with sprinklers where 150 prisoners at a time were disrobed and ordered in for a shower which never gushed forth from the sprinklers because the chemical was gas. When they ran out of gas, they merely sucked all of the air out of the room. I talked to the Jews who worked in the crematory, one room adjacent, where six and seven bodies at a time were burned. They gave these jobs to the Jews because they all died anyhow, and they didn’t want the rest of the prisoners to know their own fate. The Jews knew theirs, you see.

I saw the living skeletons, some of whom regardless of our medical corps work, will die and be in piles like that in the next few days. Malnutrition doesn’t stop the day that food is administered. Don’t get the idea that these people here were all derelicts, all just masses of people... some of them were doctors, authors, some of them American citizens. A scattered few were G.I.s. A Navy lieutenant still lives to tell the story. I saw where they lived; I saw where the sick died, three and four in a bed, no toilets, no nothing. I saw the look in their eyes. I shall never stop seeing the expression in the eyes of the anti-Franco former prisoners who have been given the job of guarding the S.S. men who were captured.

And how does the applause fit in? Mother, I walked through countless cell blocks filled with sick, dying people - 300 in a room twice the size of our living room as as we walked in - there was a ripple of applause and then an inspiring burst of applause and cheers, and men who could not stand up sat and whispered - though they tried to shout it - Vive L’Americansky... Vive L’Americansky... the applause, the cheers, those faces of men with legs the size and shape of rope, with ulcerated bodies, weeping with a kind of joy you and I will never, I hope, know. Vive L’Americansky... I got a cousin in Milwaukee... We thought you guys would come... Vive L’Americansky... Applause... gaunt, hopeless faces at last filled with hope. One younger man asked something in Polish which I could not understand but I did detect the word “Yit”... I asked an interpreter what he said - The interpreter blushed and finally said, “He wants to know if you are a Jew.” When I smiled and stuck out my mitt and said “yes”... he was unable to speak or show the feeling that was in his heart. As I walked away, I suddenly realized that this had been the first time I had shaken hands with my right hand. That, my dear, was Mauthausen.

I will write more letter in days to come. I want to write one on the Russians. I want to write and tell you how I sat next to Patton and Tolbukhin at a banquet at the Castle of Franz Josef. I want to write and tell you how the Germans look in defeat, how Munich looked in death, but those things sparkle with excitement and make good reading. This is my Mauthausen letter. I hope you will see fit to let Bill Braude and the folks read it. I would like to think that all the Wachenheimers and all the Friendlys and all our good Providence friends would read it. Then I want you to put it away and every Yom Kippur I want you to take it out and make your grandchildren read it.

For, if there had been no America, we, all of us, might well have carried granite at Mauthausen.

All my love,

F.F.