Bardig Kouyoumdjian

People who want to visit the places where the Holocaust happened have many options: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, the Shoes on the Danube Memorial in Budapest, former ghettos, or the fields of Babi Yar, to name a few.

But when it comes to the Armenian Genocide, former sites of the massacres and killings are so difficult to access most people have never been there or even seen them in pictures.

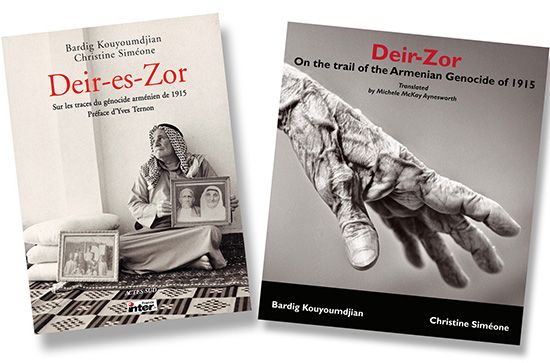

That’s what photographer Bardig Kouyoumdjian attempted to change with his book Deir-Zor: On the trail of the Armenian Genocide of 1915.

Written by Christine Simeone, the book traces Kouyoumdjian’s journey to the remote Syrian desert where hundreds of thousands of Armenians were sent to die. Kouyoumdjian also met descendants of survivors who stayed in these communities and built their lives there – sometimes without even knowing the full extent of their Armenian heritage.

One of the descendants Kouyoumdjian met and photographed was Abdel Samed Wafik Abboud, whose parents, Serpouhi Tateosi Papazian and Wafik Abboud, were both interviewed by J. Michael Hagopian for his collection of Armenian Genocide survivor testimonies. Both testimonies will be integrated and preserved in the Visual History Archive’s Armenian Genocide collection.

In 2001, Kouyoumdjian began traveling to Lebanon and Syria, focusing on Deir-Zor, the remote desert city where hundreds of thousands of Armenians had been deported and perished, to photograph the landscapes, survivors (Christian and Muslim) and their respective communities.

His black and white photographs of Deir-Zor and its surrounding areas (i.e Suwar, Shaddade, Markade, and Ras-ul-Ain) depict vast, empty deserts, underground caves and open fields where Armenians were killed during the genocide. In some places, he found bones.

“Six hours on a motorcycle and you only see horizon,” Kouyoumdjian said. “There is nothing.”

Today, just a few hundred Armenian Catholics remain in Deir-Zor, and few are aware or engaged with their Armenian background. ISIS controls the region and most Armenians have fled. Kouyoumdjian said his Armenian guides were reluctant to take him out into the desert killing sites because it was “too far.”

“It’s almost forgotten by the Armenians,” he said.

Kouyoumdjian’s book is the first to depict the places in Deir-Zor where the massacres of the Armenian Genocide actually happened, he said. And, in the 15 years since he began taking the photographs, most of the people depicted in them have moved from the area or passed away – so his photos are really all we have to remember these places.

“It’s not like Auschwitz; you don’t have traces. You are in front of emptiness,” Kouyoumdjian said. “But at least now we have pictures of the emptiness.”