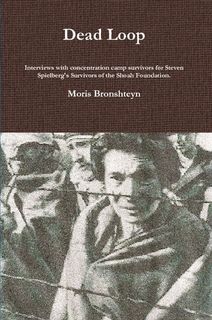

Moris Bronshteyn

Dead Loop, a new book written by Holocaust survivor Moris Bronshteyn, was born out of a promise he made to the other survivors he interviewed for USC Shoah Foundation.

Bronshteyn, an engineer from Ukraine who now lives in Walnut Creek, Calif., was invited to be an interviewer for USC Shoah Foundation, then-titled Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation, in 1994 when it began collecting interviews with Holocaust survivors in Ukraine. He had done public advocacy work on Jewish issues in the Vinnitsa region of Ukraine - never as an interviewer - but he agreed to participate and ended up conducting 74 interviews. He also gave his own testimony, although it mostly covered the experiences of his family members, since Bronshteyn himself was born in 1941.

The experience made a strong impression on him, Bronshteyn said, despite the difficulty of hearing the survivors’ tragic experiences.

“I was happy and unhappy at the same time,” Bronshteyn said. “Unhappy from multiple experiences with the survivors. Happy being involved in the important and noble cause together with the team of the Shoah Foundation.”

Many of the survivors he interviewed had been interned in the Djurin ghetto and Pechora concentration camp, which some historians refer to as the “Ukrainian Auschwitz.” Tens of thousands of Jews died there at the hands of Romanian authorities (Romania was allied with Germany), and most of these perpetrators were never brought to justice.

“We all, at the beginning and end of the interview, promised that their [testimony] will become available to the general public in the world,” Bronshteyn said.

Bronshteyn watched testimony at Stanford University, the only Northern California site with full access to the Visual History Archive. He transcribed the testimonies and included his own comments. It was very important to him that the book be translated into English as well, so that more people could read it. Dead Loop can be purchased here.

“Always I believed and believe now, that the Holocaust is relevant, especially today,” Bronshteyn said. “People need to know the consequences of [conflicts waged on] ethnic, racial or religious grounds.”