Why are dozens of streets in New Jersey named after Oskar Schindler?

Her father, Abraham Zuckerman, had lost his entire family during the Holocaust and wanted his children to have an extended family, something he himself was denied. So he created a new one, one that included the man who had saved his life and whom he dedicated the rest of his life to honoring: Oskar Schindler. “I didn’t know who he was,” Katz said. “My father would say, ‘Uncle Oskar would be so proud of you.’ That’s all I knew. Oskar Schindler was the only family I thought I had.”

The paths of Oskar Schindler and Ruth Katz would intertwine many times over the years, both in personal visits he made to the family home in New Jersey, and even after his death, when Katz traveled to Israel with her father when he participated in the final scene of the film “Schindler’s List,” which was directed by USC Shoah Foundation founder Steven Spielberg. In the iconic ending of the movie, real Holocaust survivors saved by Schindler visited his grave with the actors who portrayed them in the movie.

She said it was a surreal being with all those people who, like her father, were saved by Schindler.

“It was a once-in-a-lifetime experience,” Katz said. To see all these people pay tribute to this man and to walk next to the actors who portrayed them. They were alive because of Schindler. I can’t even explain what kind of experience it was for my dad. What Spielberg did making that movie was report what really happened.”

For Abraham Zuckerman, it was an experience a long time in the making. In the decades after the Holocaust, it wasn’t uncommon for survivors to avoid talking about what happened to them. They wanted to protect their children’s innocence and spare them the pain of knowing what their parents endured. The Zuckerman family was no different.

“The survivors never really wanted to talk,” Katz said. “They didn’t want to talk about the bad things that happened in their lives. They wanted to move forward. They wanted their children to have the happy life they didn’t have.”

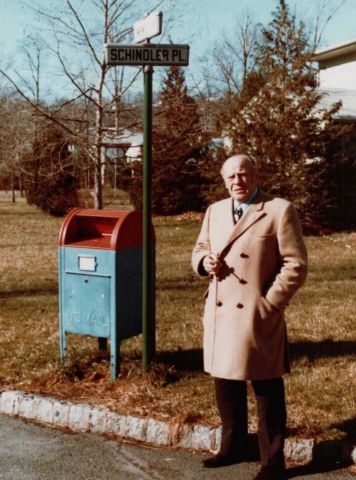

But even before he explained to his family exactly who Oskar Schindler was – and before his name became well known – Abraham Zuckerman worked hard to honor his legacy. As a successful developer, Zuckerman made sure that every new housing division contained a tribute to Schindler.

“The first street was always named Schindler Drive or Schindler Avenue,” Katz said.

The Northeast is dotted with such thoroughfares – there are 24 streets named Schindler in New Jersey – but it wasn’t until the film was released that residents discovered the mystery behind the names.

“Now, all of a sudden, people living on Schindler Drive started calling the news,” Katz said.

Zuckerman also helped provide financial support for Schindler until he died in 1974.

He chronicled his story in the 1991 book, “A Voice in the Chorus: Memories of a Teen-Ager saved by Schindler.” The family was also instrumental in the publishing of USC Shoah Foundation’s 20th Anniversary book “Testimony: The Legacy of Schindler’s List and the USC Shoah Foundation,” which was dedicated in honor of Ruth’s parents Millie and Abe and in tribute to Oskar Schindler. The book chronicles the making of the film, as well as the establishment and evolution of the Shoah Foundation, which was founded by Spielberg in 1994 after his experiences making the movie.

Zuckerman died four years ago, but in a 1992 article in the New York Times, he described his good fortune of being selected to work in Schindler’s enamel factory after enduring life in seven concentration camps.

“The minute I came to the factory, life changed,” he said. “There was food, mountains of potatoes. You were never hungry. Moreover, we didn’t do that much work.”

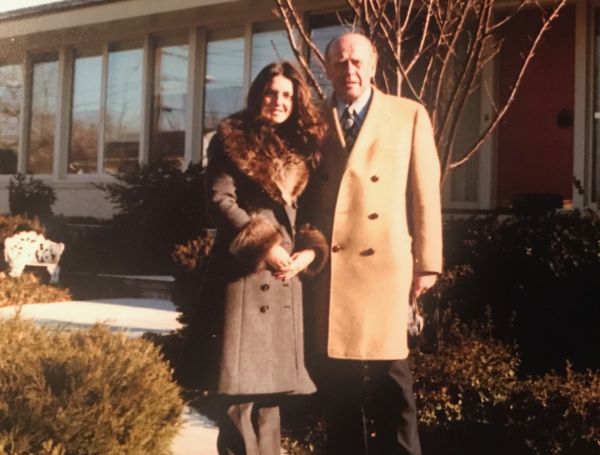

When she got into her teens, Katz not only learned the real story behind Uncle Oskar, but finally met the man who loomed so large in her family’s history.

“When I was about 12, my dad started talking about him,” she said. “I was 14 or 15 when he came to my home.”

She remembers him as being larger than life.

“He was very tall, handsome, kind, soft spoken and endearing,” Katz said. “He was so happy that my father had my sister and brother and me. He was so happy my father was surviving. He would come to our house and say, ‘You are my children.’ To me, he was the grandfather I didn’t have.”

It’s been 25 years since “Schindler’s List” was released. During a special screening to commemorate the anniversary in New York in April, Katz was once again able to meet many of the people involved in its production. And her mother, Millie Zuckerman, who was ill during the filming in Israel, was able to attend the screening with her. Millie, who survived the Holocaust by going into hiding, had always kept a low profile.

“In 65 years of my life, my mother never wanted recognition,” Katz said. “She didn’t want to be in the forefront.”

But when she went to the New York screening, she was embraced by everybody involved in the movie. And it was at that moment that she truly understood the importance of her family’s history.

“When Steven (Spielberg) saw my mom, he put his arm around her,” Katz said. “She did not feel the impact until then.”

As the Institute prepares to commemorate its 25th anniversary later this year, Katz remains grateful to those who risked so much to protect others.

“When I went to the movie in April, I was able to watch it with all my children,” she said. “Life is good.”