Building Dams and Bridges

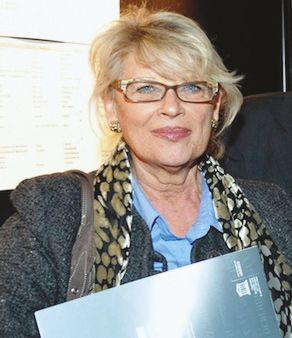

The Aladdin Project, which was founded in 2008, aims to dam the spread of Holocaust denial, antisemitism, and racism in the Muslim world, and simultaneously erect bridges to renew relations between Jews and Muslims. Founder Anne-Marie Revcolevschi reflects on her journey to turn the symbol of Aladdin’s lamp as a tool of magic into a symbol of knowledge, stemming ignorance, obfuscation, and extremism.

It all began with the virulently antisemitic and revisionist statements by Iran’s then-president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and his hate speech against Israel, which dramatically worsened the already tense relations between Jews and Muslims, not only in the Middle East and North Africa but also in Europe and North America. It was then that I discovered, to my utter dismay, that none of the classic texts on the Holocaust had been translated either into Arabic or Persian. Time was of the essence, as the tide of hatred grew, and so together with an esteemed group of colleagues, including Simone Veil and David de Rothschild, we tackled the problem head-on and began to translate and distribute translations. Essential to this effort was building an international network of intellectuals and political figures, the majority of them hailing from Muslim cultures, on the basis of shared values and common objectives.

The response to our initial activities vindicated the underlying assumption of our endeavor: that sharing knowledge and education can transcend differences and reconcile people. Today the Aladdin Project’s multilingual website is in five languages and has received hundreds of thousands of visitors; more than 80,000 copies of our 18 books in Arabic and Persian, including The Diary of Anne Frank, If This Is a Man by Primo Levi, and The Destruction of the European Jews by Raoul Hilberg, have been downloaded from Aladdin Online Library, showing that readers, users, and especially the younger generations are willing to learn as long they are given the opportunity.

Encouraged by these results and supported by a large number of European and international personalities, in 2010 we decided to move closer to Muslim public opinion and organized an unprecedented series of conferences about the Holocaust in 10 cities: Cairo, Casablanca, Rabat, Baghdad, Erbil, Istanbul, Jerusalem, Nazareth, Tunis and Amman. Several thousands of people attended these meetings, listening to an array of speakers that included historian and Nazi hunter Serge Klarsfeld, filmmaker Claude Lanzmann, peace activist Ali El Samman, veteran diplomat Jacques Andréani, the king of Morocco’s adviser André Azoulay, among others. Reading Primo Levi in these places changes the landscape of learning and dialogue in the Middle East.

The rise of political Islam and its associated racism, and the outbreak of domestic and international crises complicated our task. Yet this is precisely the time to act: Young people and those yearning for freedom in the countries of the so-called “Arab Spring” want to learn about the world around them and be able to share the values of freedom and respect for others.

It was then that we turned to add film to our growing catalogue of content. We began with translating Claude Lanzmann’s masterpiece documentary, Shoah, into Turkish and Persian, and telecast the film for the first time in Turkey and Iran. More than 10 million viewers watched the movie, which was broacast by Turkey’s national television channel, TRT, and the Los Angeles–based, Persian-language Pars TV. Many viewers in Iran contacted Pars TV to express their surprise and incomprehension: How could this reality be denied by their leaders?

Reaching deeper into higher education is part of a strategy to maintain high-level learning and dialogue. Under the leadership of Executive Director Abe Radkin, who organized Aladdin’s first summer university at the University of Basheçehir in Istanbul in partnership with 16 prestigious universities in Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and the United States, fifty-six American, African, Arab, European, Israeli, Iranian, and Turkish students worked together on the history of mass violence in 20th-century Europe and the challenges facing European societies today. They attended conferences with lecturers from around the world, which offered a unique opportunity for bright young people from different countries and cultures to focus on the causes of the Holocaust, the consequences of hatred, and rejection of the “other, ” the transition of a Europe torn apart by two world wars to peace and reconciliation. The graduates of the summer university were appointed “Youth Ambassadors for Peace and Intercultural Dialogue” and in April 2014, the best groups were recognized for their research by the Aladdin Award at the European Parliament. The next Aladdin university will be held this summer in Berlin.

To sustain this drive for education in the Muslim world, the training of teachers is a priority. In November 2013, in cooperation with the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, Aladdin organized the first international training seminar on the Holocaust for teachers and scholars of the Muslim world.

In the Muslim world, where people face the realities of violence and extremism, it requires strength and determination to work toward our objectives. In truth, my trust is based on the knowledge that I was born in Paris in 1943 and only survived thanks to the courage of a French family that hid me and my mother. Those small points of light never stopped flickering during the dark days of the Nazi period. Now the light of knowledge, the source of Aladdin’s lamp guides our way, as we put up dams and build bridges in dark times all over again. The testimonies of the USC Shoah Foundation are a part of that same light of knowledge, which we hope to share in the languages of the Muslim world together, inspired by the same desire for truth among peoples of different cultures and religions.

USC Shoah Foundation’s Executive Director Stephen D. Smith was keynote speaker at Aladdin’s teacher’s seminar in Istanbul. A joint project with Aladdin to transcribe and translate USC Shoah Foundation audio-visual testimony into several languages of the Middle East is now under way, including testimony about Auschwitz, which was used during this year’s International Holocaust Remembrance Day on January 27.