Historic Photos of a Little-Known Outdoor Jewish Ghetto

The following is a summary of a collection of photos depicting the mass migration to an open-air ghetto outside of the small city Kutno, Poland, in 1940. The summary was written by Julia Werner, an advanced doctoral candidate in history at Humboldt University of Berlin, who discovered the photos at the Jewish Museum in Rendsburg, a small museum in the former synagogue of Rendsburg dedicated to the history of the local Jewish communities and German-Jewish history. The photos were taken by Wilhelm Hansen, a German Wehrmacht soldier who later became a member of the Nazi Party. Werner came to the USC Shoah Foundation Center for Advanced Genocide Research on a fellowship in February 2016 to deepen her understanding of the ghetto by reviewing testimonies of people who were held there. Werner was the 2015/2016 Margee and Douglas Greenberg Research Fellow.

Click here to view her lecture on the topic at USC.

(All photos taken by Wilhelm Hansen. Source: Jüdisches Museum Rendsburg in der Stiftung Schleswig-Holsteinische Landesmuseen Schloss Gottorf.)

On the day of the ghettoization of the Jews in Kutno in western Poland in June 1940, Wilhelm Hansen, a German teacher and Wehrmacht soldier, took a series of 83 photos. The picture above is one of his last shots of the day.

This shot might be a good starting point - a “punctum” so to say - as the image shows the end result of the ghettoization that happened on that very same day and gives an idea of the desperate situation of the Jewish population: left on the premises of an abandoned sugar factory outside the city center with a good share of their belongings, out in the open with nowhere to live and nowhere to put their furniture in this open-air ghetto. The image challenges how we usually imagine a ghetto, as the setting is very much different from those in known ghettos such as Warsaw or Łódź/Litzmannstadt, where the ghettos were set against the backdrop of cityscapes, with narrow streets, houses, markets and crowded squares.

There has been a lot of research on ghettoization policy, mainly based on perpetrator documents: population policy and the ghettoizations are seen as a form of social engineering and a history of competing institutions, for example the question of what the dominant motives were (such as the prevalence of ideological vs. economic motives). But the actual results of the racist population policies of the Nazis, the effects on the everyday lives of people are usually not central to these debates: what leaving apartments and belongings behind meant and what it looked like – emotionally as well as practically. Also visually, these moments of transfer have not been part of the established group of the same images that are being used in publications and exhibitions over and over again. There are a few publications on the big and rather well-known ghettos in Warsaw in Łódź/Litzmannstadt that look into different aspects of the everyday lives of the inhabitants, using photographs as well as diaries and other documents, but much less so on smaller ghettos and nothing on the ghettoizations, the move itself. There are publications on life in the already established ghettos, but most of the historical research is focused on structural questions like the function of the ghettos in the context of NS-population policy. Therefore photography and the example of Hansen’s collection of images are perfectly suited to really look into this central moment in so many people’s lives, that has been overlooked so far.

On the photographer and the collection

Christmas 1939, Poland. (Hansen is the one standing to the left.) Photographer: Wilhelm Hansen. Source: Jüdisches Museum Rendsburg in der Stiftung Schleswig-Holsteinische Landesmuseen Schloss Gottorf.

Wilhelm Hansen was born on January 9th 1898 in Schleswig, a small town in the north of Germany. The photo above shows Hansen and his fellow soldiers celebrating Christmas 1939 in Poland. (Hansen is the one standing to the left) Hansen lived with his mother in a villa in a small village next to Schleswig. After his mother died, he moved in with his sister. From 1936 he worked as a teacher at the Cathedral school in Schleswig; he taught geography, English and French. Wilhelm Hansen was drafted to the Wehrmacht, the German army, right after Germany attacked Poland, on September 5th 1939.

Hansen applied for membership in the National Socialist German Workers Party, or Nazi Party, on July 29, 1941, about a year after he had taken the photos of the ghettoization in Kutno. He was officially accepted on October 1st, 1941.[1]

His former students and colleagues describe him as a loner and somewhat bizarre, but generally friendly. He was a passionate photographer way before his time as a German Wehrmacht soldier in Poland and his students and colleagues remember him with a camera at almost every occasion.

After WWII he discovered super-8-film cameras and started to document the local life around Schleswig, gatherings of the local rifle associations, goat breeders, etc. It is unclear and impossible to reconstruct what his motivations were. What we know for a fact is that he didn’t do much with his filmic and photographic material; he archived it and kept it mostly to himself. It is only due to a fortunate coincidence that we have access to these photos today. Jan Fischer, an archeologist and collector who was dealing with Hansen’s sisters house and her belongings after her death, came across his photographic collection and identified their value. Today you can find about 800 of Hansen’s photographs from the Warthegau in the archive of the Jewish Museum in Rendsburg.

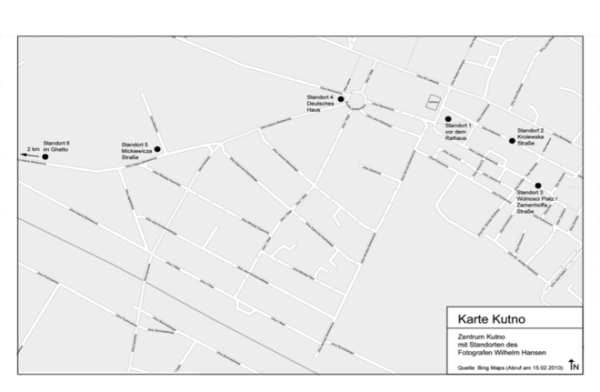

Hansen took a series of 83 photographs on the day of the ghettoization of the Jews in Kutno on June 16, 1940. He basically spent all day documenting the forced move and “accompanying” the people who had to move their belongings to an abandoned sugar factory around 3 km outside the city center, where most of the Jews in Kutno lived. Kutno had a Jewish population of 6,700 by the beginning of WWII -- about 25 percent of the overall population. The series gives us an idea of the whole process of the ghettoization. The photos also enable us to reconstruct the way to the ghetto and the stops Hansen made along the way. From these photos, we can infer that Hansen moved around freely and did not try to hide his camera.

[1] Bundesarchiv Berlin, ehemals BDC (Berlin Document Center), NSDAP Zentralkartei, Mitgliedsnummer Wilhelm Hansen: 887502.

Kutno map with Hansen's route

In the city center of Kutno in the morning

Photographer: Wilhelm Hansen. Source: Jüdisches Museum Rendsburg in der Stiftung Schleswig-Holsteinische Landesmuseen Schloss Gottorf.

Photographer: Wilhelm Hansen. Source: Jüdisches Museum Rendsburg in der Stiftung Schleswig-Holsteinische Landesmuseen Schloss Gottorf.

Photographer: Wilhelm Hansen. Source: Jüdisches Museum Rendsburg in der Stiftung Schleswig-Holsteinische Landesmuseen Schloss Gottorf.

On the way to the abandoned sugar factory, 3 km outside the city center

Photographer: Wilhelm Hansen. Source: Jüdisches Museum Rendsburg in der Stiftung Schleswig-Holsteinische Landesmuseen Schloss Gottorf.

Photographer: Wilhelm Hansen. Source: Jüdisches Museum Rendsburg in der Stiftung Schleswig-Holsteinische Landesmuseen Schloss Gottorf.

Photographer: Wilhelm Hansen. Source: Jüdisches Museum Rendsburg in der Stiftung Schleswig-Holsteinische Landesmuseen Schloss Gottorf.

Photographer: Wilhelm Hansen. Source: Jüdisches Museum Rendsburg in der Stiftung Schleswig-Holsteinische Landesmuseen Schloss Gottorf.

One of the entrances to the ghetto

Photographer: Wilhelm Hansen. Source: Jüdisches Museum Rendsburg in der Stiftung Schleswig-Holsteinische Landesmuseen Schloss Gottorf.

On the premesis of the abandoned sugar factory "Konstancja"

Photographer: Wilhelm Hansen. Source: Jüdisches Museum Rendsburg in der Stiftung Schleswig-Holsteinische Landesmuseen Schloss Gottorf.

Photographer: Wilhelm Hansen. Source: Jüdisches Museum Rendsburg in der Stiftung Schleswig-Holsteinische Landesmuseen Schloss Gottorf.

Photographer: Wilhelm Hansen. Source: Jüdisches Museum Rendsburg in der Stiftung Schleswig-Holsteinische Landesmuseen Schloss Gottorf.

Photographer: Wilhelm Hansen. Source: Jüdisches Museum Rendsburg in der Stiftung Schleswig-Holsteinische Landesmuseen Schloss Gottorf.

Hansen’s photos give us a good sense of the whole process of the forced move. And as much as his photos do help to bring out new aspects and perspectives, one of the main problems of working with photographs from the time of the German occupation of Poland (1939-1945) is that there are almost no photos that were taken by Jewish Poles or Catholic Poles, because the Nazi occupiers tried to control the means of production and therefore the access to photographic means of production was very asymmetrical: Jews were not allowed to own cameras, and the use for non-Jewish Poles was strictly limited to the private sphere. The German occupiers not only disowned photo labs owned by Poles and banned Polish professional photographers from employment, but also confiscated private cameras.

Ingo Loose, a leading researcher in the field of Holocaust studies, has argued there was a camera ban in all Polish ghettos, as very few photographs exist in which Jews had any influence over the production, motif or distribution.[1] Therefore it is important to keep in mind that the photographical sources that have come upon us today are mostly perpetrator and bystander photographs. This particular set of photos at Kutno was taken by a privileged Reichs-German who was part of the occupying force; his perspective is reflective of that.

And the mere act of taking a photo itself in that situation adds yet another layer of violence to the situation. Photography, the creation of a representation of this act of violence, of this forced move, extends this act of violence and humiliation. Even though photography was not a very common practice back then as it is today (in 1939 around 10 percent of the German population owned a camera), it is safe to assume that there was an awareness and understanding of the photographic situation on both sides.

Only going beyond the pictorial frame can bring back the agency of the photographed. This is also why the interviews with survivors in the USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive are an enormously valuable source in addition to the photographs – they help to bring back the voices and the individuality of the Jewish men, women and children being ghettoized, in order to be able to see beyond pictorial frame. They help to broaden the perspective on the process and also put the people being ghettoized more in the focus; they enable us to see more and help to make certain aspects visible, that would otherwise remain invisible.

For example, Gordon Klasky -- who was born in 1915 in Lubraniec, Poland -- spoke at length about the establishment of the ghetto in a 1995 interview conducted by USC Shoah Foundation:

“It was on a Sunday, June 16 1940. They came out and ordered. It was on a Saturday night, almost Sunday. […] The Germans gave that order to the Jewish population that everybody has to report the next day to a certain place and this was called -- it used to be a factory that made sugar -- and it was called in Polish Konstancja. And over there that Sunday we were allowed to take whatever we could, you know. […]

What were you allowed to take with?

"Furniture, whatever, you know, you couldn’t take any dogs or cats, so furniture you could take along with you, you know, and tools, most things we left. While we were taking our stuff, they used to… the mayor from the city, his name […] his name I remember exactly…he was an SA man […] he used to wear that brown uniform with an Hakenkreuz and his name was Sherman and he was walking through the Jewish homes and he used to beat us and he used to take out everything, you know. Fast, fast, you know. He used to beat us over our heads …and fast fast…you know: schnell.” [2]

The photographs do not only make the individuality of the people being photographed invisible, but also the violence of this forced move. Because of the absence of acts of violence as well as uniformed men and spectators/ bystanders, at first sight the photographs do not convey the impression of a forced move, but more of a self-organized move or process. So the photos help to bring out the importance of the moment of the ghettoization, open new perspectives, like in the case of the Kutno ghetto which shows an – from our perspective today – unusual ghetto, but at the same time, they make the force and violence that happened “invisible."

Click here to watch a clip of Klasky's testimony

Klasky then goes on:

“So that Sunday they took us to that ghetto. It was a big place, you know, and I was forced, at least somehow I got into that big place, maybe a thousand people. We put the beds close to each other […] there was no place where to walk, just to lay down on the bed. […] There was a lot of people who didn’t have any place any more. I remember that day there were toilets there and they cleaned it out and they lived in that toilets. That’s the truth. And then a lot of people put up like a little house you know, like the Indians have […] like tents, but built from wood and they put blankets on top and they got in over there. It was raining and we were swimming, that’s right. Then you see, they needed barbers and I am a barber and we got together all the barbers and we put up there our mirrors on the walls […] and we used to work, you know, cut peoples’ hair when the weather was nice. When it started raining it was terrible.”[3]

Here, the connection of photographic and oral sources allows the viewer to look beyond the pictorial frame, and gives an idea of what happened outside the picture that day, as well as what happened before and after the photograph was taken. Yet another photograph taken by a German soldier after the establishment of the ghetto shows a barber stand in the Kutno ghetto, maybe even the one that Klasky mentioned.

Click here to watch a clip of testimony from another Kutno survivor, Barbara Stimler.

Summary

The photographs of Wilhelm Hansen, a German Wehrmacht soldier, help to bring out aspects about the ghettoization of the Jews in Poland that have often been overlooked. They draw attention to an unusual ghettoization – or at least one very much different from the ones known from popular images of the “big” ghettos in Warsaw, Litzmannstadt and Krakow, which are published over and over again and show ghettos against the backdrop of a cityscape, with houses, crowded streets etc.

The series of 83 images by Hansen makes the ghettoization of the Jews in Kutno tellable. No other sources allow us to talk about the ghettoization in such detail: horse carts, people waiting, the large amounts of things, belongings, furniture, etc. that people were able to take to the ghetto in that particular case, the perception of the ghetto space filled with people and belongings that are – from Hansen’s perspective – almost impossible to distinguish, the desperate situation on the premises of the sugar factory at the end of the day, when around 7000 people were basically just left alone there with their belongings.

On the other hand, the photographs also reproduce the perpetrators’ perspective. The VHA interviews offer a perfect addition here. The two different sources have different qualities: Hansen’s photographs, as they are photos by a German perpetrator or at least bystander, focus on the process of ghettoization, his focus is not on the people being ghettoized, but more interested in the process on a “documentary” level. They de-humanize people – the process of ghettoization does that in the first place of course – but the photos of the ghettoization seen through the eyes of the perpetrators, who keep a distance and do not focus on the people perpetuate that. In the process of ghettoization the Jewish population was forced into being a group and the photos reinforce that: they homogenize a diverse group of people.

The interviews from the Visual History Archive, on the other, help us understand the context of the moment of ghettoization better from the perspective of the Jewish people who were forced to move that day. They help us refine the context and also give us a much better understanding of the concrete situation of the individuals being subjected to this forced move and the diversity of people and experiences. They therefore help to take a much more differentiated look at the situation of the people being ghettoized. The interviews manage to convey a much more complex perspective on the very heterogeneous group of people that the photographs tend to homogenize for the viewer. They bring out the unique and diverse voices of the survivors and help to present a more detailed and multi-perspective historical narrative.

Click here to read a scholarly summary of Werner's work by Martha Stroud, Ph.D., the research program officer at the USC Shoah Foundation Center for Advanced Genocide Research.

[1] An exception is the Getto Łódź: Loose, Ingo, Ghettoalltag, in: Hansen, Imke, Steffen, Kathrin und Joachim Tauber (Hg.), Lebenswelt Ghetto.

[2] Klasky, Gordon, Interview. Visual History Archive. USC Shoah Foundation. Internet. 28.11.2014. (http://www.vha.fu-berlin.de).

[3] Interview Gordon Klasky, Visual History Archive, Freie Universität Berlin, www.vha.fu-berlin.de