My Keynote at the UNESCO Latin American Convening on Teaching with Testimony

In 1993, filmmaker Steven Spielberg was shooting Schindler’s List. The Cold War had recently ended and Spielberg was shooting in Poland—a former Soviet bloc nation. Now that the walls were down, survivors of the Holocaust were going to Poland to retrace their steps, find their roots. From time to time, survivors turned up on the movie set, curious to find out what was going on. Spielberg invited them onto the set, and spoke to them. From those conversations came Steven’s idea to create an opportunity for survivors of the Holocaust—and others who witnessed it in different ways—to share their life story. Back in Los Angeles, he hired some young producers to work out how to take testimony of eye-witnesses around the world. It was an audacious plan. 50,000 testimonies were gathered in 56 countries in 32 languages. This effort required several thousand volunteers and videographers, training sessions for interviewers, and networks of people dedicated to finding survivors and giving them the opportunity to share their story, about their own lives, in their own homes, in their own language. They spoke in front of the video camera for an average of 2hours and 12 minutes, sharing their painful life history for the benefit of memory, education and understanding—as a lesson to the world.

These survivors testimonies included Ana Benkel de Vinocur, born in Lodz, Poland, who survived Auschwitz and Mauthausen. She gave testimony in Montevideo, Uruguay:

The archive was taken in 56 countries, 21 of which were in Central and South American. Ana is just one of the 1,352 who chose Spanish as their language of choice, while another 560 chose to speak Portuguese. The team that collected those testimonies were all local people in the communities where you live and work, part of a global volunteer network who knew that the stories that people were telling in Montevideo, Santiago de Chile, San Jose Costa Rica, were just as vital to have in this archive as those living in Paris, Berlin or New York. Why? because their adopted countries were as much a part of their life as all the nightmares that had preceded them [led them there]. In fact, those countries played a very significant role in their lives—they are the places that took them in and gave them refuge, security, dignity, humanity, a name and a place to finally call home after they had been driven from their homes.

Let us take a quick look at where the testimonies were gathered among the countries from which you come:

But this is not the whole story. These folk were interviewed in your country, but many others also talked about your countries, even when they were interviewed elsewhere. Perhaps they came to your country first, then moved on. Maybe they have a surviving relative there. Maybe they came on business, or even described a fabulous vacation! Each time a witness refers to a place they went to we document that specific place as a keyword in their testimony. And so if we look at how many times your countries are spoken about in the archive, this is what we see.

As you can see, there are 11,084 one-minute segments which have your country as a keyword in the Visual History Archive.

If we add in the other Central and South American Countries, we get a grand total of 13,164 one minute segments that discuss some aspect of living or visiting South America, by people who survived or were direct witnesses of the Holocaust and Genocide.

Think for a moment about just how difficult it was for these people to share the darkest moments of their lives with us. The vast number of participants in the archive is deceptive, because each one had to think long and hard about whether they would open up their lives or whether in fact it was safer for them to remain silent. Let’s listen to Moises Flasterstein from Lublin, Poland. He survived Majdanek and five other camps and gave testimony in Costa Rica.

Let’s discuss Manfred Stein, from Romania, who survived the Storojinet ghetto and was interviewed in Santiago, Chile. In his testimony, Manfred grapples with the relationship between preserving history and overcoming contemporary genocide.

Manfred acknowledges that his story will become history and seems unafraid of this inevitability. I am intrigued, though by the link he draws between remembrance and action. He commands us, ‘Don’t forget!’ His assumption is that if we remember, then it will be less likely [(for us) to repeat] in the future. Notice he does not command us to ‘Remember!’. Instead, he commands us ‘Do not forget!’ Is there a difference? Well actually, yes. Remembrance has passive overtones of reflection and looking back. Being commanded not to forget [Refusing to forget] is active, present and carries [responsive to dangerously real] implications. In other words, if you do forget, you are not learning the lessons and one day may well suffer the same fate. In other words, if you do forget, you are failing to learn the lessons that may well one day save you from suffering the same fate.

Some survivors of the Holocaust who moved to South America did experience a second round of violence in their lives. Sheine Maria Sara Rus from Lodz, Poland, survived the Auschwitz and Mauthausen concentration camps, migrated to Paraguay, and then made her life in Buenos Aires.

For all of their tenderness, I don’t think for a moment that these people are providing a soft approach to genocide. Scheine is a self-defined fighter. She uses the term, ‘fight’, when she says, ‘I will not stop fighting’. Is she fighting back against those who wronged her? Seeking revenge? She has every right. But no, she is fighting for humanity. With so much violence in the world, the strength of these gentle souls is often overlooked, as is the fact that we ourselves could draw strength from them if we took more time to listen. Somehow it is the dictators with the nuclear weapons as in North Korea, the savage religious extremists in ISIS, the makers of war and terror in Syria that grab our attention. They create harm, of which we are afraid. If we had more fighters of our own like Scheine Maria Sara Rus, maybe we would be less afraid, and maybe we would overcome the ideologues and the extremists more easily. Make no mistake—this archive is also an archive of resistance. Resistance which says, ‘I am still alive even though someone tried to murder me.’ Resistance which says, ‘my story will take its place in the world as a force for good over evil.’ Resistance against the idea of genocide itself.

Elena Boguslavsky from Vilna, Poland survived in hiding and was later interviewed in Mexico:

‘Punches.’ Think about that word she chooses. ‘Punches.’ Her life has been forged by punches. Her reference is to the hardening of steel, but there is an equivalent process that shapes our personality through suffering. Life hits and hits and hits us, but we become stronger through it. That is what we call resilience. Elena knows how hard life can be. And note, she is another survivor that uses that word ‘fight’. In this case her fight is to overcome challenges that are thrown our way personally. She is encouraging us to mobilize our resolve in the face of evil and disappointment to overcome evil behavior. She is emulating another fighter that says, “use the punches to your advantage.” Become stronger as a human being. A fighter that has completely disregarded the weapons of war, avoided revenge and rejected hatred. Instead, Elena urges us to avoid the mob, and always use our individual power of reason.

You may notice that each of these interviewees so far are Jewish by background. These clips I have shown were in response to the question, ‘What is your message for the future?’ Notice that they all speak to universal principles. They do not focus on themselves, or on their community. They focus on the things that have shaped them, from which any of us can learn or adopt, no matter our background or experience.

The Visual History Archive was established to share the story of humanity as told by those that experienced the Holocaust. And our collections are growing. We now have collections of testimony from survivors of the Armenian genocide of 1915-1923, the Nanjing Massacre in China in 1937, Cambodia in 1975-79, and Rwanda in 1994—with plans to incorporate testimony from Darfur, Bosnia, and Indonesia in future years.

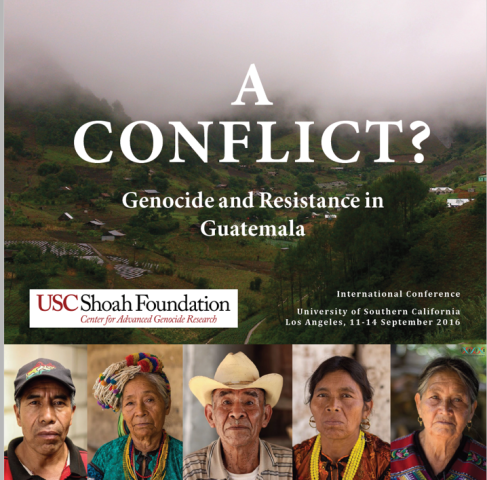

Our latest interview collection is from Guatemala. I went to Guatemala for the first time just two years ago to learn more about what happened during the Rios Mont years in Guatemala during the early 1980’s. During that trip I witnessed the beautiful work carried out by our collection partner, the Foundation for Forensic Anthropology in Guatemala, whose efforts include exhuming bodies that have been unidentified for 35 years, carrying out lab investigations, conducting DNA research, providing evidence for criminal trials, and then returning the remains to families and communities in order to guarantee a dignified burial among their people. Together, we are documenting the stories of those who survived. Over 150 testimonies have been taken, with new ones being added every day.

Thank you, Fredy Peccerelli and your remarkable team, for the work you do in pursuit of justice and education.

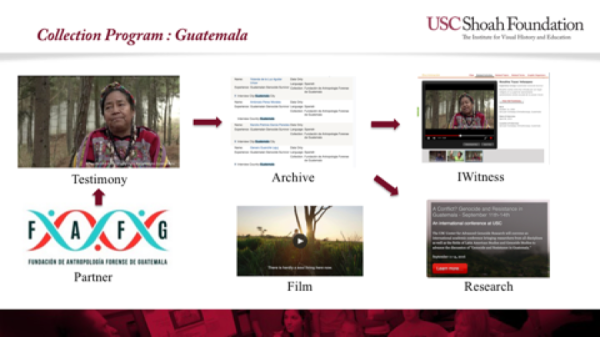

Testimonies are so much more than personal story. This weekend as we launch the first few testimonies from Guatemala, we are demonstrating the many ways in which the story becomes a part of our defense against genocide. We start by taking testimony of individuals;

Then, they are integrated into the Visual History archive.

This provides material for scholars to study, which in turn provides the opportunity to conduct research; hence the international conference we are holding on the latest research about the genocide in Guatemala.

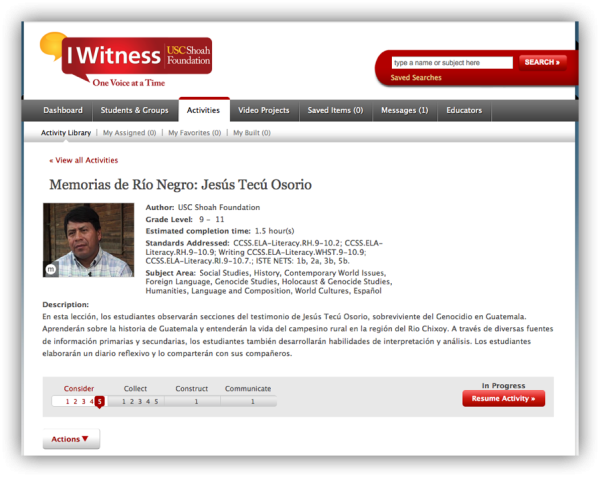

From there, we integrate the testimony into our schools’ educational platform IWitness so that students can explore testimony and learn lessons in our classrooms.

And to get the attention of the world we usually create a film, which opens the door for curiosity and interest in the topic.

And so testimonies do not stand alone, but are part of a program of collection, research, education and global outreach.

When I was in Guatemala for the first time I had the honor of meeting survivor, spokeswoman on women’s rights, and parliamentarian, Rosalina Tuyuc. Next week, she is the guest of honor and keynote at our conference. These are a few words from Rosalina’s moving testimony which she gave at the site of the memorial she created.

It is another time and another place, but the resilience of Rosalina resonates with what we have heard before - inner strength, learning to survive as we overcome death. Eleana Bugoslavsky spoke about the mob, Rosalina talks about the abuse of power crushing the weak. She too is a fighter, and makes clear that her weapons are her word and her work and her commitment to life.

As we begin our deliberations and learn together over the next two days, these brave souls who have experienced the worst of human violence will be our guiding lights. You see they did not give us a life history. This is their life, and our role is to take the treasure of their resilience, their strength, their insight and wisdom and to turn it into a powerful resistance in the fight against evil in our world, through the power of our commitment to life.