Dr. Ruth’s journey: from “Holocaust orphan” to worldwide fame

In the 1980s, a tiny woman in her 50s named Ruth Westheimer shocked and delighted the world with her blunt advice – delivered in a grandmotherly German accent – about sex. She became a media sensation and remains a household name as “Dr. Ruth.”

Less known is her perilous journey to get there – a story that includes her survival of the Holocaust and immigration to British-controlled Mandatory Palestine, where she briefly became a sniper in a Jewish paramilitary force.

Westheimer’s early life history is explored in a new IWitness activity that uses clips of testimony she gave to USC Shoah Foundation in 1998.

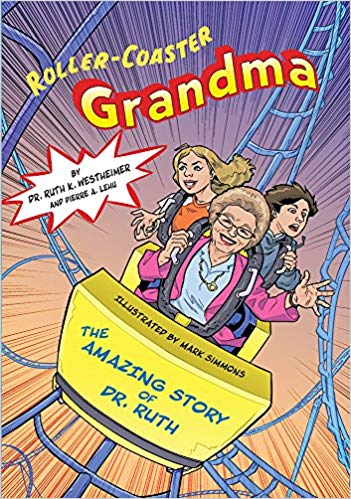

Called “Info Quest: Dr. Ruth Westheimer,” the new learning activity for students in grades five and six accompanies the newly released illustrated memoir “Roller-Coaster Grandma,” which follows Westheimer’s visit with her teenage grandchildren to an amusement park, rendered in bright colors and comic-book style. Each activity they face, however, prompts a sepia-toned story from her past – from her childhood train ride to safety in Switzerland to her years in an orphanage, through her brief tenure with paramilitary forces in Jerusalem to her decades as an educator and media personality in New York.

They coincide with another project, an upcoming Hulu documentary called Ask Dr. Ruth, which will weave the story of her traumatic childhood with her rise to fame as a sex therapist whose 1980s radio show, “Sexually Speaking.”

Given their young targeted audience, the children’s book and accompanying activity focus on Westheimer’s childhood experiences and not on how she became a household name. In the book, when Westheimer peers into a funhouse mirror at the amusement park with her grandkids, she sees her father in her own stretched-out smile. This triggers a memory about the last time she really saw him: the day after Kristallnacht, when Nazi soldiers stormed into their little apartment in Frankfurt, Germany, and dragged him off to a labor camp.

“They came very early,” Westheimer says in a clip of testimony used in the new IWitness activity. “I remember looking out the window and seeing my father going into a truck, and turning around with a very faint smile, and waving.”

Westheimer – who attended USC Shoah Foundation’s board meeting in April -- was born Karola Ruth Siegel in 1928. She turns 91 on June 4. In a clip of testimony on IWitness, she describes her life in an Orthodox family prior to the Holocaust: “I was rather spoiled,” she says. “I remember that I had 13 dolls. I remember that I had rollerskates. I know that I was the only child.”

After the abduction of Westheimer’s father, her mother sent the 10-year-old girl to Switzerland via the Kindertransport. Westheimer never saw either parent again, and believes they died in the Holocaust.

“I don’t think of myself as a survivor,” she says in her testimony. “I think of myself as an orphan of the Holocaust.”

After years in a Swiss orphanage, Westheimer immigrated to British-controlled Mandatory Palestine in 1947. She joined the Haganah, a Jewish paramilitary force that later became part of the official Israeli military.

“That wasn’t an act of heroism on my part,” she told USC Shoah Foundation. “Everybody was a member of the Haganah. Because by that time, it was clear that everybody had to know to be armed and to be able to defend the country.”

She quickly became a proficient soldier.

“By now I knew how to fire a (sniper) stun gun, knew how to put it together with my eyes closed -- I knew how to throw hand grenades,” she says in her testimony.

On June 4, 1948 – her 20th birthday – Westheimer was stationed to work surveillance from a rooftop when a war siren sounded. She went inside. A shell crashed through the building. Some people inside died; shrapnel pierced both of Westheimer’s legs.

“Somebody took my shoes off, and I said, ‘Do I have to die?’” she recalls in her testimony. Westheimer underwent surgery and recovered in a hospital. During her brief stint as a soldier, she never shot anyone.

Westheimer was intellectually restless. In 1950, she moved to France with her first husband. He was a med student; she worked as a kindergarten teacher to pay for her own schooling in psychology at the Sarbonne.

She would teach at the University of Paris for several years before relocating to the United States in 1956 and earning a master’s degree in sociology from The New School – a private research university in Manhattan -- and a doctoral degree in education from Columbia University.

“I was eager to learn, once I liked the subject matter,” Westheimer says in her testimony.. “I went to all of the seminars, I went to all of the conventions, I gave papers. And when I got my doctorate in the study of the family, I started to teach at the university.”

She lived in New York with her second husband, but has said that her most meaningful relationship was her third marriage to Manfred Westheimer, a Jew who’d also escaped Nazi Germany as a child and migrated to the States.

They met on a ski trip in the Catskill Mountains in New York -- atop a slope.

“Somebody introduced me to Fred and said, ‘He is the president of the Jewish ski club,’” Westheimer said. She was charmed that weekend by his harmonica skills and how he wore his World War II military uniform when skiing the slopes. They married in 1961 and had two children. They were married until his death in 1997.

Westheimer grew fascinated with human sexuality as a staff member at Planned Parenthood in New York, and began working as a professor and postdoctoral researcher with pioneering sex therapist Helen Singer Kaplan.

At the height of the AIDS epidemic, Westheimer started broadcasting frank advice about sex and relationships, spinning her interest into a media career that in 1983 would start to see widespread success. Soon, she found herself on everyone’s late-night television screen, speaking seriously to giggling hosts on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson and Late Night with David Letterman during sex-advice-charged interviews.

In the illustrated memoir, the cartoon version of Westheimer tells her grandchildren about the importance of finding one’s voice – and alludes to how her German accent proved a vital part of her persona.

“Plus, I think everyone liked my show because I was honest!” Westheimer’s cartoon says. “I listened to people’s problems and gave them practical ways to solve them.”

“Plus, you were funny,” says her grandson.

“Yep,” Westheimer concurred. “That helped, too!”