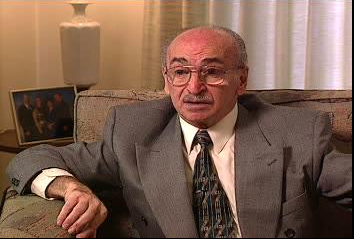

In memory of Holocaust survivor Jack Welner, who became soulmates with his USC Shoah Foundation interviewer

We are saddened to hear of the recent passing of Jack Welner, who survived a Jewish ghetto in Poland, a labor camp near the Dachau concentration camp in Germany, and the Auschwitz Nazi death camp in Poland – where his mother was murdered on arrival – before immigrating to Denver, Colorado, where he began a new life. He was 98.

When Welner gave his testimony to USC Shoah Foundation in 1995, it changed his life.

It not only enabled him to bear witness to the atrocities he experienced firsthand, but also led to an important relationship in his life. He and his interviewer, Lori Goldberg, were strangers on that November day, but they formed an instant connection, and became lifelong friends. The obituary published by Welner’s family referred to them as “soulmates.”

“Whichever chapter of life we were in – joyful times or challenging times – we were there for each other,” Goldberg, also a Denver resident, told USC Shoah Foundation earlier this month, not long after his death on August 28th – two weeks before his 99th birthday. “It was a connection not completely of this world.”

Over the years, the two friends spoke together in classrooms about the Holocaust, attended symphonies, celebrated holidays, went on trips, shared many meals, and had daily conversations.

“The Shoah Foundation gave us this blessing, and we cherished it,” Goldberg said.

Friends remember the carpenter and father of three as a jovial presence who still drove a car to play poker with his friends at the Jewish Community Center in Denver until just before his death.

“He’s very positive, very happy – always easy going,” said John Pregulman, a photographer who took portraits of Welner and other Holocaust survivors. “He liked to tell jokes – mostly dirty jokes.”

Welner was forced by the Nazis to live in a small room with seven family members in the ghetto, brutally beaten at slave labor camps in the woods near Dachau in Munich, quarantined with delirious prisoners who were dying of typhus, and suffered from ulcers from performing heavy labor in a state of near-starvation. And yet he credits a friendly German soldier for saving his life.

Born Jacob Nuta Welniarz on Sept. 10, 1920, in Lodz, Poland, Welner remembers growing up with four siblings in an environment where attitudes towards Jews like himself – even before the war – were hostile.

“I wouldn’t dare venture into a non-Jewish neighborhood,” he said. “I would have gotten beaten up.”

His father, Joshua Welniarz – the operator of a newspaper stand in Lodz – died of an illness in 1930. After Joshua’s death, the 10-year-old Welner and his 14-year-old brother used to operate the stand.

The family was among 160,000 Jews forced into the Lodz Ghetto. They packed their belongings on a sled and pulled it to what became their home – a room with no plumbing or heat, and where their breath was visible in the winter.

“We all slept together to keep warm,” he told Goldberg, the interviewer, in his 1995 testimony that lives in the Visual History Archive.

Welner’s older brother, Samual Welniarz, died of starvation on June 6, 1944 – coincidentally on D-Day.

Two months later, Welner was deported to Auschwitz with his mother and a sister. Each was given a piece of bread and some margarine for the trip; Welner ate his right away. Just after the train doors were thrown open into the chaos of Auschwitz, his mother, Esther Welniarz, pressed the piece of bread into his hand.

She told him to take it because he’d need it.

“That was the last I saw of her,” he said, his voice breaking.

After about a week in Auschwitz, Welner was among 150 starving Jewish men transported via boxcar to a labor subsidiary camp of Dachau to work for the notorious military engineering firm Organisation Todt. They arrived to find hundreds of well-fed Lithuanian Jews already working there. The Germans beat Welner and the other new arrivals for their inability to carry as much weight.

“There’s an old saying,” Welner said, “'a man who is well fed doesn’t believe that somebody is hungry.'”

Welner remembered pounding wooden stakes into the ground with a sledgehammer as an officer hit him on the back. Knowing he had to do something to get out of the situation – lest he die of exhaustion – Welner dropped to the ground and started crying. As the officer screamed at him to get up, Welner thought to himself, “I will survive you.”

Welner’s luck changed for the better, due in no small part to his assertiveness.

One day, he approached a German machinist at the camp and offered to work for him. The machinist – who, like many older Germans, worked behind enemy lines – turned out to be humane.

He brought Welner extra food. Every morning, the machinist – Mr. Stefan – gave him a newspaper to read. And when Welner was plagued by ulcers, the machinist let him lie down out of sight to recover.

“I would lie behind the machine and he would cover,” Welner said. “I would say, ‘Mr. Stefan, I will never forget you.’ … He was a real human being – what we would call a mensch.”

In April of 1945, as the Allied Forces closed in on Dachau, Welner was among thousands of prisoners who were forced on a death march. On May 1, after one week of marching, he and the other surviving prisoners awoke to find that most of their captors had vanished.

The prisoners walked to the small German village of Waakirchen; Welner found a barn and buried himself in hay for warmth. The next day, May 2, the Americans arrived. They tossed cans of food from moving Jeeps.

After the war, Welner settled in Denver to live with an uncle. In 1951 he visited a close friend in New York. On that trip, he met a young woman named Adele. Jack and Adele hit it off immediately; they married six weeks later and moved to Denver.

In 1958, Adele fell sick and died, leaving him with three young children.

“I came back to the house, and I said to the children, ‘Mommy went to heaven and she won’t come home anymore,’” he said.

The next year, he took them to Israel to live in proximity to his sisters.

Despite all he has been through, Welner described himself as an eternal optimist.

“I see the bagel, not the hole,” he told the Glendale Cherry Creek Chronicle, a local newspaper near Denver, in May of this year.

The article also includes a photo of Goldberg on Welner’s fireplace mantle, among his other family pictures.

Earlier this month, Goldberg told USC Shoah Foundation she’ll never forget the day of the interview: Nov. 9, 1995.

During a filming break to change tapes, she remembers thinking to herself, “Lori, your life is never going to be the same.”

Goldberg wrote about their connection in an article for the autumn 2010 edition of PastForward, a digest published by USC Shoah Foundation.

“One of the most important lessons that Jack has imparted is that you can’t let the past ruin your future; life goes on,” she wrote. “His imperative to others is that we use memory as a motivation to do good things in the world.”

He is survived by his three children, six grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.