My Reluctant Encounter With the USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive

I never intended to spend months listening to Holocaust testimonies.

My name is Chaya Nove, I am a sociolinguist working on a doctoral dissertation about language change in Yiddish vowels. In my research, I consider the Yiddish spoken by Hasidic Jews in New York today (Hasidic Yiddish, or HY) as a living, changing language, with the understanding that this language was once spoken by a group of people in another time and place.

In my study of language variation and change, I am examining the ways in which the sound of vowels, and the position of the jaw and tongue in producing them, have changed across generations and geographies. To trace the change and compare the differences, I could not only rely on spoken Yiddish in New York today. I also needed to find acoustic evidence of spoken European Yiddish.

New York Hasidic Yiddish speakers largely trace their ancestry to the historical Unterland region of pre-war Europe, highlighted (approximately) in the pink on this map (Image 1).

Image 1 (above): Map of Eastern Europe, with the approximate historical Unterland region highlighted in pink. (Google n.d.)

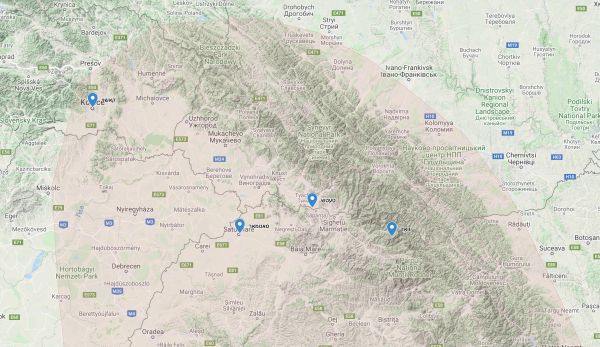

As it turns out, I’m a typical representative. My own grandparents were born and raised in the places marked on the map in Image 2.

Image 2 (above): Map of the Unterland region, with Kosice (קאַשוי), Satu Mare (סאַטמער), Tyachiv (טעטש), and Vadu Izei (װאַד) marked in blue. (Google n.d.)

Unfortunately, by the time I began to study Yiddish linguistics, three of my grandparents were already deceased, and the fourth had severe dementia. Moreover, very few of their contemporaries were in a condition to be interviewed for this type of study.

My quest to find recorded speech of Yiddish speakers from this region led me to the USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive, where, to my delight, I was able to conduct a search by region and find over forty testimonies, in Yiddish, of speakers from the European Unterland, including a distant cousin I did not know I had.

Now there was a personal hurdle I needed to overcome: The environment in which I grew up was permeated with stories about the war. By the time I had children of my own, it had become too difficult for me to hear, read, or even think about these things. Instead, I tended to shield myself emotionally from most things Holocaust-related. Yet here I was, embarking on a project that would have me listening to hours and hours of survivors’ testimony.

So, I procrastinated for a while. When I did finally start listening to these recordings, I learned that, rather than focusing exclusively on their war experiences, survivors were prompted to describe, in great detail, their lives before the war. Instead of being bombarded by horror stories of suffering and death, I was instead invited into the personal, familial, and cultural lives of these people in a way I had never been before. As I listened to one testimony after another, these survivors, whom I had previously thought of as ‘grandparents’ and ‘seniors’ became recognizable, through their drives and dreams, as individuals just like me and my children.

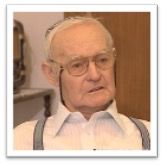

One of the first testimonies I encountered was by Meyer-Mano Daskal, who was born in in 1906, in Satu Mare (Szatmár in Hungarian,) where my paternal grandfather was also born and raised.

Image 3 (above): Meyer-Mano Daskal, born in 1906 in Szatmár (presently Satu Mare, Romania)

A terrific storyteller, Daskal talks about how he succeeded, against all odds, in purchasing his dream home shortly before the war began. It was a large house on ‘the Hill of Szatmár’, encircled by a vineyard on one side, and fruit trees (pears, plums, apples) on the other. As he describes the property, and his intense desire to acquire it, his voice comes alive and his face lights up. He is transformed. It is the voice of a 20-year-old who is awake to everything that life has to offer.

Daskal tragically lost his wife and children in the war. It goes without saying that he also lost his dream home. As one mentally adds these (comparatively) minor heartbreaks to the larger, more abstract scenes of annihilation with which we are all too familiar, the sense of loss becomes excruciatingly acute.

Incidentally, when I first listened to this, my own children were in the process of buying their first home. I felt as though time had collapsed, like I could actually see these survivors as they were, in the world that was.

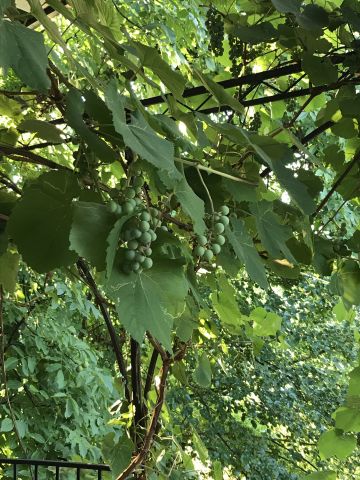

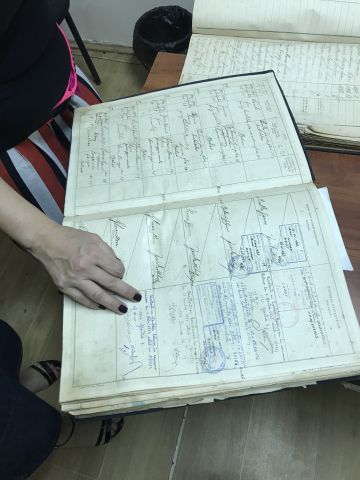

Prior to my encounter with the VHA, I couldn’t pinpoint where Satu Mare was located on a map. Now, I wanted to know everything about prewar life in this region (not merely the quality of the vowels). I started reading every available monograph about its history and, in the summer of 2018, I took a trip to Romania to visit my ancestral towns and villages: Satu Mare (סאטמער), Sighetu Marmatiei (סיגעט), Tyachiv (טעטש), Vadu Izei (װאַד), and others. There, I tasted those plums, apples and grapes that Daskal had loved; visited the graves of my ancestors; scanned old records; and met some wonderful locals.

Through the VHA, I was connected to a part of my ancestry and my people that had been invisible to me before. I am only sorry that the voices of my own grandparents were never preserved in this way.

My vowel study continues, but I’m already planning my next project, which will hopefully bring these (and other) Yiddish testimonies to a larger audience.

Image 4 (above): In the Jewish cemetery in Satu Mare (סאַטמער), Romania, August 2018

Image 5 (above): With some local Satu Mare ladies, dressed in their traditional holiday attire

Images 6, 7 and 8 (above): Plums, apples and grapes grow wild and abundantly in this region

Image 9 (above): Examining civic records in Vadu Izei, Romania

Images 10 and 11 (above): In the Maramures countryside, with views of the Carpathian Mountains