Rena Quint, Child Survivor, Found Herself In Her Family History

When Rena Quint was 31, a cousin from Israel came to visit her in New York. She hadn’t seen or spoken to a blood relative since she was 7 years old.

“Oh Fredzia, do you remember your sister?” her cousin asked, using her Polish name.

“No, I didn’t have sisters,” Rena told him. “I had two brothers, Dovid and Yossi.”

“Oh, you were so cute, such a little girl, with your sisters,” Rena recalled her cousin, who was older, saying.

Rena went home devastated. She didn’t remember having had sisters, but she did remember her brothers. She remembered them pulling her on a sled through the streets of Piotrków – not far from Łódź, Poland – on wintery Fridays, a pot of chulnt nestled beside her, ready to place in the bakery oven to stew overnight for a hot Shabbat lunch. She remembered seeing her mother and brothers for the last time, at around six years old, when she slipped out of a Piotrków synagogue where Nazis had rounded up hundreds of Jews. And she remembered saying goodbye to her father when he entrusted her to a schoolteacher as they climbed out of a cattle car and women and children were sent one way, men another.

But over the decades, she began to doubt her own memories. Did she really remember her brothers? She recalled her parents’ names, the feeling of their presence, but she couldn’t conjure up images of their faces. Over the years so many people had questioned how such a young child could have survived the Bergen Belsen Concentration Camp without parents that she began to suspect even her most visceral memories of the stench, the lice, the cold and hunger.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that she started to seek and find answers in repositories of Holocaust documents, in conversations with other survivors, and in Polish archives.

It was in a records hall in Piotrków that she found her birth certificate, and those of her brothers—but no others. This confirmed that her memory, not her cousin’s, was in fact true.

"Every time you find something, you prove to yourself that it was real, and you start to believe things,” Rena said in testimony she recorded for USC Shoah Foundation in 1998.

She framed her brothers’ birth certificates and hung them in her Jerusalem home amid the photos of her children and grandchildren. But, after some time, she took them down.

“I found it difficult to pass by. As much as you don’t want to ever forget, you can’t remember all the time,” she said in her testimony.

Rena is now 86 and still serving as docent at the Yad Vashem World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem. She was one of two survivors to meet with President Joe Biden when he visited Yad Vashem in July 2022.

Rena has worked hard to find a balance between moving beyond memory and living inside of it, between yearning to know—and have proof of—where she came from and what she lost, but of not wanting to be defined by it.

Ready to Confront Her History

Rena said in her 1998 testimony that for most of her early life, she had no interest in revisiting the past.

In 1946, 10-year-old Rena had been adopted by Leah and Jacob Globe in Brooklyn, New York. They gave her everything she had lost during the Holocaust—a new name and identity, aunts and uncles and cousins and a secure and loving Jewish home. She learned English, jumped to grade level at her Jewish day school, earned a college degree and became a teacher. She married and had four children of her own.

“I never wanted to tell anyone I was survivor, or that I was adopted, or that I was different,” she said.

By the time her children were mostly grown, Rena felt ready to confront and understand her past. In 1981 she and her husband, attorney Rabbi Emmanuel Quint, traveled to Israel for the first World Gathering of Holocaust Survivors. It was there that she met other survivors from Piotrków and learned to access new research tools.

She knew that her birth name was Fredzia (Fraidl in Yiddish) and that her parents’ names were Yitzchak and Sara Lichtensztajn. But in the bank of computers at the gathering, she found no trace of her family. A docent explained to her that the information in the databases of victims and survivors had been supplied by family members who had survived. Rena realized that it was up to her to enshrine her family’s memory.

Rena then wrote to the Arolsen Archives, an international clearinghouse located in Germany that contains millions of documents related to Nazi persecution.

In response, Arolsen researchers sent her a copy of a registration card from a Displaced Persons camp. It had her name on it and confirmed that she had been in the Piotrków ghetto and in Bergen Belsen Concentration Camp. She then attained documentation from the Swedish government, as she had been hospitalized in that country after liberation. And at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York, in a book of names of survivors of Bergen Belsen Concentration Camp, she found, “Fredzia Lichtensztajn, 9 years old, Poland.”

A Return to Home and Memory

In 1989, Rena and her husband took a trip to Piotrków.

Clerks in the municipal records hall helped her find a trove of information: her own birth certificate, her brother’s birth certificates, and her parents' marriage certificate. For the first time she learned her mother’s maiden name, Messer, and that she was named for her grandmother, Fraidl. She also learned her real date of birth, which fell two months before the one she’d adopted upon arrival in the United States.

She found the address of her childhood home, and she went to visit the site. She saw the balcony she remembered, and could picture the kiosk across the street where she always got ice cream. On the doorpost of her former home she found a faint outline of a tilted rectangle under many layers of paint—the mezuzah her parents had hung as a talisman and prayer to protect the home.

Even before her visit, Rena had recalled the moment in 1939 when strangers moved into her home. On her tour through Piotrków, she observed that the synagogue, the bakery, and the Jewish schools were all located close to her home—all within the confines of the ghetto established by the Nazis. She learned that the Piotrków Ghetto was the first ghetto of its kind in Poland, set up in October 1939, just one month after Germany’s invasion of Poland.

She also visited the Piotrków synagogue, which had been turned into a library. A librarian took her to a space where, hidden behind a bookshelf, she saw the Ark where the Torah scrolls had once been kept. The Ark’s doors, adorned with the Ten Commandments, were pocked with bullet holes.

“I Don’t Know if God Pushed Me”

Rena had long known about the roundup at the synagogue, both from her own memories and from accounts of other survivors. While she couldn’t place the event on a timeline, many roundups in Piotrków took place in 1942. She knew she had been there with her mother and her brothers, and remembered the screaming and fear and that a man, perhaps an uncle, had signaled to her from a back door.

“I don’t know how a little girl could have been willing to run, to leave her mother,” she said in her testimony. “I don’t know if God pushed me, or if my mother pushed me, or if this man had some sort of lure. But I did run.”

She later learned that everyone else rounded up that day including her mother and two brothers, had been taken to the Treblinka death camp.

The man who had spirited her out of the synagogue took her back to her father, who then hid her in the ghetto. She remembers the darkness, the people who snuck in scraps of food, the pail that was emptied once a day. And then one day—she has no sense of how much time would have passed—her father cut her hair and told her that she was now a boy named Froim. Going forth she would live with her father in the men’s barracks at the factory where he worked.

The stench of the factory, the sludge, the sand, the heat of the furnace, she and other children hauling water to the slave laborers—all of these things remained strong in Rena’s memory. From her research and after speaking with other Piotrków survivors, she established that she’d likely lived at the Hortensia Glass Factory.

“More than anything, I remember the vicious dogs that the soldiers used to hold on to,” she said. “I have two marks on my knees as reminders of that time.”

A Missing Year, A Horrifying March

She learned from the DP card she’d attained from the Arolsen Archive that after Piotrków she had spent a year in the Polish town of Częstochowa. But she had no memory of this time, and was unable to find any other documentation to that effect. But she clearly remembered the treacherous journey to Bergen Belsen that followed, which the card informed her had ended in January 1945.

There had been no steps leading up to the cattle car, so men had hoisted her up to the train. They were not given any food, and their water came from icicles that formed on the small window frame. By day three of the journey, the floor of the cattle car was covered in dead bodies and human waste. She remembered the sudden bright sunlight when she finally climbed down from the train, and her father’s goodbye. He knew he would no longer be able pass her off as a boy, so he found a schoolteacher to care for her. He gave Fredzia some family photos and small valuables and promised to meet her back in Piotrków once the war was over. She never saw him again, and she later learned that he had been sent to Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

Fredzia and all the women and girls who had been transported in the cattle car were then marched through the snow. The subsequent lifelong pain in her toes would remind her that her feet had been wrapped in only rags as she walked. One sight from that march never left her mind: two bodies at the bottom of a ravine, their pants at their ankles. She later surmised that guards had checked to see if the runaways were circumcised.

Upon arrival at Bergen Belsen the women and girls were sent to showers, where a Nazi guard snatched Fredzia’s photographs and valuables. The schoolteacher accompanying Fredzia stole a black coat for her, and the pair slept on the cold floor of the women’s barracks on a scattering of straw that crawled with lice and rats. She longed for the potato peel soup and the sawdust bread they received in the evenings, and dreaded the mornings when they had to haul the dead bodies out of the barracks and stack them alongside the other corpses piled along the fence. When the schoolteacher suddenly disappeared, other “mothers” stepped in to care for Fredzia.

She doesn’t remember specific guards, but years later, at an exhibit at Yad Vashem, she saw a picture of two female SS guards. “That is Clara and Inga,” Rena said out loud, without knowing why.

It was only later, when Rena found her records from a Swedish hospital, that she learned that she had been suffering from diphtheria and typhus when she was liberated from Bergen Belsen by British soldiers in April 1945. She was nine years old. She has a vague memory of realizing that the zombies— her fellow inmates—were suddenly singing.

After being transferred and treated at a Swedish hospital she was told she would soon go to Palestine with other orphans and there would perhaps find distant family.

Starting a New Life

In Sweden, Fredzia met Anna Philipstahl, a German survivor whose daughter had recently died. Fredzia assumed the dead daughter’s identity—becoming Fanny who had been born in Germany in February 1936—and used it to travel to the United States with her new mother and her brother, Sigmund.

But only months after the newly constituted family arrived in Long Island, New York, Anna died. That was when “Fanny” was introduced to Leah and Jacob Globe, a Brooklyn couple in their 40s who had never had children. The Globes adopted Fredzia, and gave her a new name—Rena, the Hebrew translation of her Yiddish name, Fraidl, which means joy.

“Most children who survived had to continue their lives. If they lost their parents, they were lost forever. If they lost aunts, uncles, grandparents, there was no way of getting them back,” Rena said in her testimony. “I was different. I got new parents. I got new cousins and new aunts and uncles and new grandparents. I even got a new name and a religion. I became the person I am now, and they are the ones who molded me and shaped me.”

In 1984, Rena and her husband immigrated to Israel, where some of her children and her mother, Leah Globe, had previously settled. She taught English to Russian immigrants, and, as she dug deeper into her roots, became a docent at Yad Vashem.

At 86, she continues to tell her story to audiences everywhere—on Zoom, in person, and in A Daughter of Many Mothers, a book she published in 2017.

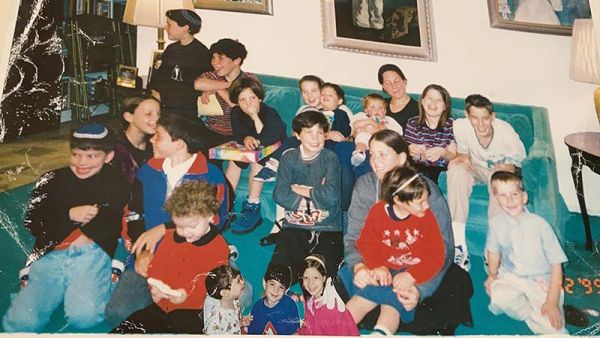

But her primary audience is her 22 grandchildren and 43 great grandchildren.

Rena’s granddaughter, Geffen Shvat, 22, said in an interview from Jerusalem that she is grateful not only that her grandmother survived, but that she has been eager to explore and share her story.

“Even the youngest grandchildren and great-grandchildren know Savta Rena’s stories,” Geffen said. “To know that our family has this history, and these roots, and to know where we come from and what her family was like and what sort of customs they had—the clearer the picture of our family becomes, the more color it adds to our lives.”