Defying Horrors of Teenage Years in Auschwitz, Joshua Kaufman, 95, Embraced Life

The USC Shoah Foundation mourns the June 6, 2023 passing of Joshua Kaufman, who survived Auschwitz and was liberated at Dachau Concentration Camp at the age of 17, and was recognized at the 2019 State of the Union address in Washington, D.C. He was 95.

Joshua’s touching reunion with the American soldier who liberated him at Dachau was captured in the 2015 History Channel documentary The Liberators: Why They Fought. In 2016, Joshua traveled to Germany to testify at the trial of former SS member and Auschwitz guard Reinhold Hanning. Joshua was not allowed to testify during the trial because of procedural rules, but he addressed the press outside the courtroom, saying he had wanted to speak to Hanning “soldier to soldier, grandpa to grandpa.”

Joshua, who served in the Israeli Defense Forces for 25 years, lost around 100 family members in the Holocaust, including his mother and his three siblings.

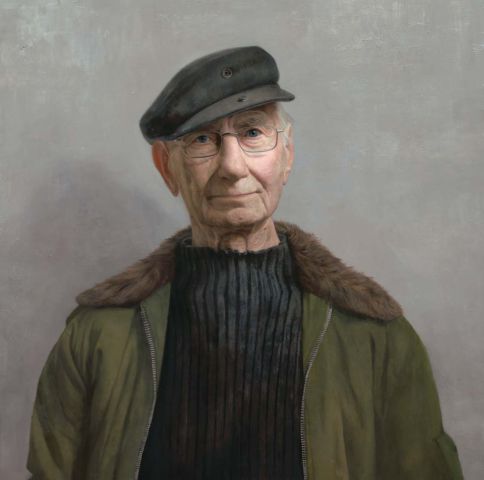

Later in life, as a father of four daughters and a professional plumber, Joshua was known throughout the Los Angeles Jewish community for his warmth and no-nonsense lust for life – a wry charisma captured by artist David Kassan in a life-sized portrait of Joshua wearing his trademark jaunty fisherman’s cap. The painting was included in Facing Survival, a 2019 art exhibition of the USC Shoah Foundation and USC Fisher Museum of Art, which paired Kassan’s portraits of Holocaust survivors with testimony from the Visual History Archive. (See the exhibit online.)

For many years, Joshua declined to speak about his wartime experience, but in 2017 he gave a 5- hour interview with the USC Shoah Foundation just as the Institute was ramping up its Last Chance Testimony Collection, an ongoing effort to capture the stories of Holocaust survivors while time and memory permit.

Joshua and his daughter were invited to attend then President Trump’s 2019 State of the Union address, along with a Jewish American soldier who helped liberate Dachau. “Your presence this evening honors and uplifts our entire Nation,” President Trump said.

A Satmar Hasidic Upbringing

Joshua was born on February 20, 1928, in Debrecen, Hungary, the third of four children of Berta and Alexander Kaufman, a successful businessman in the lumber industry and officer in the Hungarian army. The deeply religious and well-off Satmar Hasidic family lived on a large estate in Debrecen, surrounded by extended family. At the age of 11 or 12, Joshua was sent to the Satmar Yeshiva in Satu Mare, Romania, where he studied Talmud.

In 1938 and 1939, Hungary’s Nazi-influenced regime passed race laws, modeled on Nuremberg laws, that revoked Jews’ equal citizenship status and severely limited Jewish economic freedom, exacerbating existing antisemitism. Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, igniting World War II, and in November 1940 Hungary joined Germany’s Axis alliance.

With the situation growing worse for Hungarian Jews, Joshua’s family considered moving to Palestine to seek safety and join the effort to establish a Jewish homeland – but Satmar Chief Rabbi Joel Teitlbaum opposed Zionism, and forbade the family from making the move.

Kaufman pointed to this incident as one of many factors that led to his disillusionment with Hasidic Judaism. He was drawn instead to HaShomer HaTzair, a secular Zionist youth group Joshua tracked down after a rabbi warned his students to stay away from it. But Joshua did not join, because he knew his parents would not approve.

Nazi Persecution in Debrecen

In 1942, Joshua’s father, a high ranking reservist, was expelled from the Hungarian army. He came home stripped of his uniform, with a shovel over his shoulder and wearing a yellow armband with a Star of David on it.

“I said, ‘Daddy, where is the uniform?’ He said, ‘Jewish people cannot be no more soldiers. We are slave laborers,’ ” Joshua recalled.

Soon after, his father was arrested and deported to a labor prison in Russia.

With his father gone, Joshua shaved his payos (sidelocks) and told his mother he was no longer religious. He joined HaShomer HaTzair, and learned self defense with the youth group.

In 1943, the Nazi-allied Hungarian police took Joshua and his brothers as slave laborers to clean the streets after Allied bombings. In March 1944 the German army entered Debrecen. Jews were forced to wear yellow stars, and were violently rounded up and placed in a ghetto. Joshua and his family were evicted from their large house and moved into a tiny apartment they shared with 15 people. In the early summer of 1944, Joshua and his mother and siblings were loaded into cattle cars and sent to the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp.

In Auschwitz, a Constant Quest for Food

Upon arrival on what he remembered as a beautiful, sunny day, Joshua, then 16 and athletically built, was sent to serve as a laborer. His mother and siblings were sent the other way, toward the gas chambers.

As he was moved into infested, filthy barracks, Joshua’s survival instincts kicked in.

“The next step was I know that I have to survive. This was in my mind. And they used to ask for volunteers. And I was the first all the time in the barrack to go to the kapo to say I am volunteering for everything,” he said in his testimony.

Food – the lack of it and the constant quest for more – took over Joshua’s every action. He understood he needed to be strong to survive, and he needed to eat to be strong.

He endured beatings when he was caught stealing potatoes from the kitchen. When prisoners threw themselves at the high voltage fence that surrounded the camp, he volunteered to clean up the bodies, so he could retrieve any scraps they might have hidden in their clothing.

He himself never squirreled food away.

“When I had more food than [I could eat], I give it away. Make it a picnic,” he said.

His main task in Auschwitz-Birkenau, where he was interned for about three months, was removing bodies from the gas chambers.

“I did my job because I got food and I want to see what is going on. Unbelievable for a Jewish religious child from a good home, good education, beautiful parents, beautiful grandparents, good people, that I have to become a butcher [at] 15 years,” he said.

As Russian troops advanced westward toward Auschwitz, a call came for volunteers. Joshua jumped at the promise of three days’ food. He was dispatched to a death march headed for Dachau.

Liberated by American GIs

Thousands died on the 700-kilometer trek, which was partly on foot, partly by train or truck. When people died, Joshua searched the corpses for food, and took their clothing to wrap around his feet to protect him from the cold and the chafing of his wooden shoes.

After arriving at Dachau, Joshua was sent to the Muhldorf subcamp, carrying cement for the construction of an underground runway for a German aircraft factory. There, the treatment was slightly better, and there was more food, but many died doing the grueling labor.

In early spring 1945, with the war coming to an end and Germany on the retreat, Joshua and other prisoners were loaded onto a cattle car, presumably for deportation to another camp. But the train didn’t move. After several hours, an inmate boosted Joshua up to look out the window. He saw no German troops. It was a few days later, on April 30, 1945, that he spotted American tanks, and soon, American soldiers busted open the cattle car doors. They took the survivors to a field hospital, put them in clean beds with fresh pajamas, and fed them in small amounts, so as not to shock their emaciated bodies.

“They took care of us like babies. I can never forget it,” he said of his American liberators.

Finding Home, and a Homeland

Over the following year, Joshua regained his strength at the Feldafing Displaced Persons Camp in Germany. Eager to get back to Hungary, Joshua, then 18, made his way to Berlin, where he found a bar frequented by Russian soldiers. He slipped in, and quietly recited the Shema prayer until he caught the attention of a Russian Jewish soldier. After hearing Joshua’s story, the sympathetic soldier and his unit agreed to transport Joshua back to Drebecen. In his childhood home, Joshua found his father, who had returned from a Siberian labor camp. Joshua’s mother and his siblings, Malka, Tzvika, and Meir, and around 100 extended family members, had all been murdered.

His father remarried, and in 1949, facing postwar antisemitism in Communist Hungary, Joshua moved to the newly established State of Israel. He settled in the southern desert town of Be’er Sheva and joined the Israeli military, where he worked as a tractor/heavy equipment operator. Joshua fought in Israel’s wars of 1956, 1967 and 1973.

A New, Magical Life

As a tourist in the United States in 1975, Joshua met Margaret Rosenblum, a Hungarian Holocaust survivor 15 years his junior. He professed his love after their first date at Universal Studios, and asked her to marry him. A few days later she agreed. They settled in Los Angeles and had four daughters: Judy, Malkie, Alexandra, and Rachel. Joshua worked as a licensed plumber.

Joshua didn’t tell his daughters he was a Holocaust survivor until they were in high school, and even then, he shared very little, in part to protect them.

His daughters, featured in his Visual History Archive testimony, say Joshua, who was the primary caregiver because his wife was frequently ill, created a loving, happy home for them.

“They made our life magical… Every day was literally a party in our house,” their eldest daughter, Judy, said, sitting near her father at the start of his testimony. She also noted that her father taught his daughters to be strong, honing their athletic and outdoor skills and urging them to always be on the lookout for danger and ways to escape.

In his later years, at his daughters’ urging, he told them about his Holocaust experiences, and eventually shared it with others.

“It's a very big thing,” he said of his decision to record his testimony in 2017. “Because I hear the voice of the people, what they said-- Joshua, don't let us forget. And I would never, ever have believed that after these years, we still have people who don't want to forget the Holocaust.”

Margaret died in 2021 after a long illness. Joshua is survived by his daughters, Judy (Yehuda) Ledgley, Malkie (Jason) Rodin, Rachel, and Alexandra (Henry) Stern, and and six grandchildren.

Watch Joshua Kaufman’s full testimony.