Newly published book of lost Armenian towns ‘puts Armenians back onto the map of Turkey’

This byproduct of “Turkification” has posed a vexing challenge for people conducting research to locate the old places.

To restore the lost history, a California researcher named Sarkis Karayan spent decades trying to catalogue every Armenian-populated settlement in Ottoman Turkey.

The culmination of this work by Karayan – a physician who died in late 2017 – is “Armenians in Ottoman Turkey, 1914: A Geographic and Demographic Gazeteer” (Gomidas Institute, 2018).

Armenian experts are hailing the book as an important work, as it offers, among other things, the first comprehensive compendium of these lost locations – as well as an accounting of the millions of Armenians who disappeared from Ottoman Turkey during World War I.

Published in September, the 674-page book was drawn from Karayan’s manuscript, which he donated to the Institute’s Center for Advanced Genocide Research in 2016.

“Each place is a political, economic, and social reality, with a longitude and a latitude,” wrote Carla Garapedian, a journalist and film producer, in the book’s foreword. “Each Armenian town and village is a place that can never be erased from the map with a propagandist’s pen.”

Karayan’s research will be a major boon to the Institute, whose researchers are tasked with attaching search terms to video testimonies of survivors of the 1915 Armenian Genocide at the hands of the Ottoman Turks. Many of these indexing terms involve the names of forgotten Armenian villages and other population centers.

Due to the Republic of Turkey’s policies, historically non-Turkish settlements and most of their non-Turkish names – be they Armenian, Kurdish, Greek, Assyrian, Georgian or Arabic -- have been changed to fit the state’s modern imagine of itself.

The result of several decades of probing Armenian, Turkish, German and French books, maps and archival sources, Karayan’s book also sets out to take meticulous account of what happened to the Armenian population during the genocide. By his estimate, there were 2.5 million Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire in 1914; nearly 2.2 million of them disappeared during World War I.

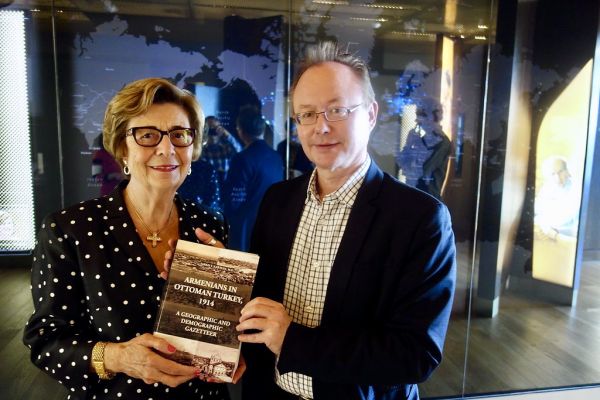

On Oct. 23, several people involved with the book gathered at USC Shoah Foundation to celebrate its publication and donation to the Institute’s Center for Advanced Genocide Research. Among them were Garapedian and Karayan’s widow, Silva Karayan – a professor emeritus of Education at California Lutheran University – as well as Ara Sarafian, historian and founding director of the Gomidas Institute in London, which published the book. Garapedian and Silva Karayan are both board members of the Armenian Film Foundation.

At the time of his visit to the Institute, Sarafian was wrapping up a book tour throughout Central and Southern California.

The last and largest stop occurred on Oct. 26 at the Western Diocese of the Armenian Apostolic Church in Burbank. The book event also doubled as a memorial to the late Sarkis Karayan with speeches from his family and performances of Classical Armenian and Opera music.

Brooks discussed the relevance of the book in relation to the Institute’s indexing research and the scope of importance gazetteers play in geographic research especially in Holocaust literature. Moumdjian and Sarafian discussed the various roles the book has in the current academic field, while Der Yeghiyan viewed the book as an important aid for Armenians and even current or former Turkish citizens to revisit and reclaim their family town or village’s roots.

“His work puts Armenians back onto the map of Turkey,” Sarafian said.