Grandfather of USC Shoah Foundation employee is a Righteous Among the Nations honoree

Franca Cassuto’s father had been cheated. The 14-year-old girl had only the capacity to watch as her father’s mistress turned him in to the fascists so she could pocket the family’s valuable jewelry once he and his daughter were gone, sentenced to die at Auschwitz.

Just a child growing up in Italy when her father’s political connections failed to protect them both from capture, Franca had no reason to expect survival. Her father, taken before her, would die before he even made it to the concentration camp. But Franca would suffer no similar fate; she was rescued with a bribe in the spring of 1944 by a relative just moments ahead of her voyage.

The relative was Alberto Innocenti, a Catholic Italian recognized posthumously by Yad Vashem as one of the Righteous Among the Nations in 2012 for his selfless wartime protection of Jewish people. Related to Franca only tenuously, he purchased her back from the very fascists that had killed her father and made a secret home for her alongside a number of other Jewish relatives whose lives might otherwise have been lost.

His own son, Franco, shared stories of his father’s heroism at a ceremony at the Florence Synagogue in 2012. Nearly 80 years after the fact, Franco’s recollection of the time is uncertain and survives in part through the questions and research of his daughter – Francesca Innocenti, a longtime executive assistant here at USC Shoah Foundation.

Francesca, who has worked at the Institute for 10 years, shared some of these stories, as well as her own memories of time spent with her grandfather, Alberto.

---

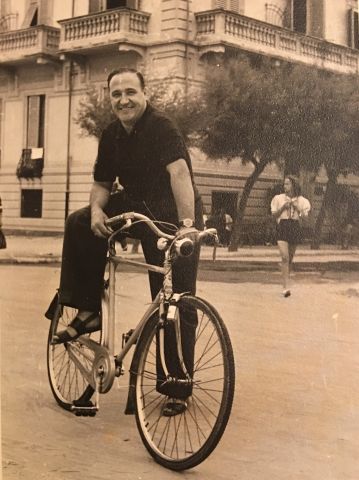

Alberto worked in a fabric store a stone’s throw from the Piazza del Duomo, a square in the middle of Florence known for its majestic Cathedral. At the store, he would fall in love with 34-year-old Bruna Servi who was older than him by six years, but more than a foot smaller and dressed in imaginative outfits that she wouldn’t come to give up until her mid-70s.

Her parents’ disapproval of her dating a blue-eyed gentile would fade as they got to know Alberto, whose own parents were uninvolved with his life and whose modest means were initially less than ideal for the Servis’ second-born daughter. The two married in 1930 and began their own family with the birth of Franco in 1931. They lived happily together in the apartment near The Duomo until racial laws came into force later that decade.

Alberto housed Bruna’s extended family and other Florentine Jews in two apartments – his own, and a vacant unit across the landing that had belonged to a family that fled to the countryside. He paid off bands of fascists with money from sold family heirlooms and paintings. He provided those he helped hide with everything, from clean fruit to haircuts to playtime on the roof for children. An early adopter of home movie cameras, Alberto shot footage of the rooftop frolics that feature the very people he is hiding. It has since been uploaded to YouTube.

Thankfully, he would think on a number of occasions, the fascists were more corruptible, less militant and set in their beliefs than the Nazis during the Holocaust. This, he believed, enabled him to save his niece, Franca, when her father’s citywide clout failed to protect their small family from capture. Alberto would raise Franca alongside Franco as his own child.

Despite the imminent danger posed by the ever-present Gestapo and armed Italian militiamen, Alberto persisted in his rescue attempts, working to make the situation less disruptive for his extended family. He snuck them all over for lunch across the way every day; placed chickens on the terrace so they could have fresh eggs. He convincingly talked away extra plate settings in front of fascists; regularly took his son to see his mother, hidden several bus stops away; and facilitated a relatively easy transition for those in hiding after the war came to an end.

And in doing all of these things, he asked for nothing in return.

---

A flood would devastate the family business more than the war had, staining all of the fabric the Innocentis stored in the basement. It would force them into retirement near Francesca’s 5th birthday in 1966. Alberto would lose his wife to emphysema in 1971. He remained in good health (diabetic but loving sweets) for another 15 years. He died in 1987 at age 85.