Hidden in the Archive: An Unknown Leaflet from a Jewish Aid Organization in 1948

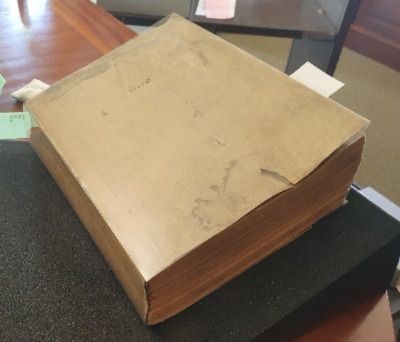

In the Special Collections at the University of Southern California Libraries there is a book – large, heavy, and musty, it contains the names of thousands of Holocaust survivors who lived in the Pest region of Budapest, the capital city of Hungary, in 1947. (Holocaust Survivors of the Jewish Community of Pest register, Collection no. 6057, Special Collections, USC Libraries, University of Southern California)

These names tell us about the people who survived the Holocaust in Hungary: those who lived through decades of right-wing regimes that redrew the relationship between Jews and their non-Jewish neighbors. They experienced the first antisemitic law in 1920; A law that introduced quotas on Jews’ place in society, schools, and universities, and which foreshadowed harsher restrictions on Jewish life in the late 1930s. When German forces occupied Hungary in March 1944, they were forced into ghettos, from which around 440,000 people were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Out of the 800,000 Jews living in Hungary before the war, an estimated 565,000 of them were murdered during the Holocaust.

This register represents, therefore, those who had endured the horrors of the Holocaust under both Hungarian and German perpetrators. It lists those who, having lived through the genocide of European Jewry, sought to rebuild their lives after the War. I first opened this book during my time at the USC Dornsife Center for Advanced Genocide Research as the Breslauer, Rutman, and Anderson Research Fellow in March 2022. When I did so, I expected to find out what it could tell me about the ages of Holocaust survivors in the city; as well as their names, the register recorded their years of birth, their occupation, and their addresses. Instead, opening this book led me on a research journey to discover a new organization I knew nothing about and to understand their charitable work in Hungary both before and after the Second World War.

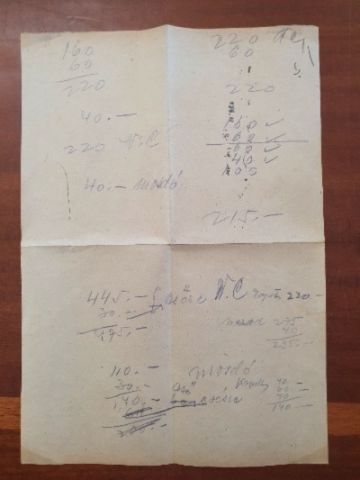

Tucked away on page 133 of this book was a folded sheet of loose paper. On the piece of paper were the scribbled notes of a previous user of the book: mostly numbers, lines of mathematical workings out, the remnants of someone’s work to understand the scale of the names recorded in this register.

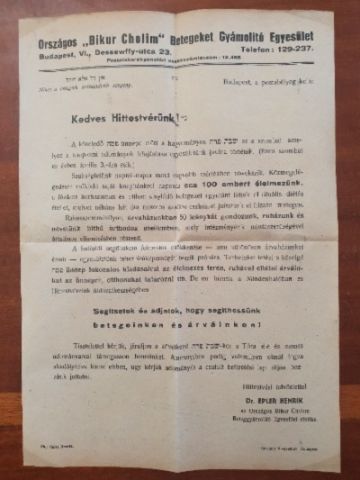

But that was not all, for this was a piece of scrap paper – a sheet that, by the time the mystery author of these scribblings came to use it, had already served another function. On the other side of the sheet from the scribblings was a leaflet advertising the work of the Orszagos "Bikur Cholim" Beteggyámolitó Egyesulet, the National "Bikur Cholim" Patient Care Association. This leaflet calls for donations and explains some of their work in the capital.

Little information exists about this organisation. Its name is significant – the Hebrew phrase ‘Bikur Cholim’ refers to the Jewish mitzvah, a religious duty, to care for and extend aid to the sick. In a video testimony for the USC Shoah Foundation’s Visual History Archive, Holocaust survivor Jozef Gabor spoke about his membership of a Bikur Cholim group in the north-eastern Hungarian town of Fehérgyarmat before the War. He explained how they were the ‘people who take care of the dead and try to take care of the sick’ (Jozef Gabor Interview, VHA/16860, seg. 19.) Indeed, it appears that the phrase was used commonly as the name for groups that visited and cared for the ill. Records from the Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives show regional groups of Bikur Cholim in eight locations across Hungary – Bonyhad, Gyöngyös, Kapuvár, Keszthely, Körmend, Nyírbátor, Óbuda, and Pápa – visualised here on this map (Schweitzer József (ed.), Magyarországi Zsidó Hitközségek: 1944 Április: A Magyar Zsidók Központi Tanácsának Összeírása A Német Hatóságok Rendelkezése Nyomán (Budapest: MTA Judaisztikai Kutatócsoport, 1994).

While the leaflet in the register book belonged to a national version of this – of which I have not been able to find any trace in the archives – it contained, printed at the top of the leaflet, an address in the capital: Budapest, VI. Dessewffy utca 23. This is the address of the Dessewffy Street Synagogue, the eldest continuously operating orthodox prayer-room in the city. It opened in 1870, when it was transformed from a horse stable, and at some point became the headquarters of the Bikur Cholim association (Dessewffy Street Synagogue, Autonomous Orthodox Jewish Community of Hungary, http://maoih.hu/en/synagogues/dessewffy-street-synagogue/, last accessed 31st March 2022.) It continues to this day as a working synagogue, with daily prayers.

The leaflet that once came from this building is undated, but was probably printed in 1948. We can infer this from some of its content and historical context. When calling for donations, the leaflet informs us that it will soon be Shabbat Parah, one of the sabbath days in the preparation for the Passover celebration. ‘This year’, the leaflet says, Shabbat Parah will fall on ‘Saturday 3rd April’. Due to the shifting days and dates of the calendar, the only years upon which the 3rd April fell on a Saturday were 1943, 1948, and 1954. The last of these dates is unlikely, as many Jewish organisations were banned under the Communist regime. Given the subject matter of the leaflet and its placing in the 1947 register, it is most likely that the leaflet dates to 1948.

When it calls for donations, the leaflet outlines the work that the organisation was doing in Budapest. We learn that they were feeding 100 people every day, taking special dietary foods to those in hospital, and running an orphanage in Rákosszentmihály (a neighbourhood in Budapest) for 50 girls. Describing more about this orphanage, they explain how ‘we look after, clothe, and raise [the children] in the faithful Orthodox spirit’. These activities concur with the work to help the sick that Jozef Gabor spoke about in his testimony from the pre-war group in Fehérgyarmat and show the broader characteristics of the Bikur Cholim as a Jewish charitable organisation. Its existence both before and after the Holocaust is significant. In a part of history that is so often focused on persecution, resistance, and conflict, recognising everyday Jewish activities brings life and richness to our understanding of communities that were targeted. In fact, Bikur Cholim groups continue to exist around the world today.

While providing food and meals to the sick fit well with the broader picture of Bikur Cholim in 1940s Hungary, the orphanage may hint at an intersection between the group’s work and the Holocaust. There is no evidence that other Bikur Cholim groups in pre-war Hungary ran orphanages, but there is a strong history of Jewish children’s homes in Budapest in the years immediately following the Second World War. These homes housed children and teenagers who had been made orphans and homeless by the Holocaust, their parents often having been killed. The Visual History Archive contains countless examples of children’s homes run by Jewish organisations, often Zionist ones and Zionist youth movements. Remembering her time in one of these homes in Budapest, run by the Women’s International Zionist Organisation, Friderika Arato recalled how ‘teachers came in, they taught us Hebrew, English, and general knowledge they wanted us to know’. The existence of a Bikur Cholim orphanage, and their expressed aim to instil in their children a ‘faithful Orthodox spirit’, suggests a point of similarity between the Zionist and Orthodox groups, as the Jewish community sought to rebuild after genocide, investing in their youth as a future generation.

This was the Bikur Cholim: a Jewish organisation with a long history, working to support those in need. At the time that my mystery scribbler received the leaflet, Bikur Cholim was providing essential support to Jewish children in Budapest, survivors of the Holocaust themselves. Children are omitted from the register of Jews in Pest, where the average age of those recorded is between 50 and 55. The leaflet therefore provides an important corrective, adding – while not the voice of youth themselves – a voice about young people. We will probably never know who the author of these scribbles were, what their connection to the Bikur Cholim was, and how this leaflet came to be hidden inside the book. But the information we can learn from it illuminates for us the life of a Jewish community in Budapest and beyond; one staying true to its values while also responding to the needs of the present.